Loneliness, Mortality and Terror

Okay, folks! Strap in for an extended philosopher file, where we’re talking about fundamental problems in philosophy, why there may be no such things, what it might mean to approach philosophy more like an anthropologist, and how to redraw our maps of human life.

Several years ago, I attended an academic conference on philosophy. Some way through the conference, mid-afternoon, at the point when everybody was becoming a bit somnolent, I found myself in a half-empty university teaching room, my notebook in front of me. In front of the room stood a tall, Norwegian philosopher. He had an air of philosophical gravity, and he spoke with a slow, careful precision. “I am going to talk about the fundamental conditions of human existence,” he said. I turned the page on my notebook, understanding that matters of such importance deserved a new, fresh page.

The philosopher started to list these fundamental conditions, of which there were three in total. “Existential loneliness,” he said. He paused. I wrote those two words down in my notebook, in capitals, underlining them twice, for good effect. The philosopher continued. “Impending mortality,” he said. Again, I wrote it down, nodding to myself seriously. “And…”, the philosopher added, leaving the best until last, “exposure to the terror of existence.” This, too, I wrote down.

As the talk continued, the philosopher carefully expounded on these three fundamental conditions of human existence. And the more he talked, the more restless I became. I found myself wondering: Were these really the fundamental conditions of human existence? And if they were, who said so? On what grounds?

The talk came to a close. After the talk was the afternoon break, and I was desperate to get out into the sunshine for a few moments. But before then, the Norwegian philosopher was taking questions, and I found myself with a burning question that I wanted to ask. So I put up my hand.

I’m never good in these circumstances. I’m not assertive enough. I am awkward and lack confidence. So several other people got there before me, asking the philosopher to say more about terror, loneliness and mortality. The philosopher was most obliging in this respect. And then, just as I thought I had a chance to ask this burning question, then the chair called the session to a close, and we all dispersed.

In the break, I went to track down the Norwegian philosopher, but he had already disappeared. And I never got a chance to ask the question. As a result, it has stayed with me. As a question, it feels awkward, even somewhat naïve. But it has continued to haunt me. The question is this: are loneliness, mortality and terror really the fundamental conditions of human existence? Or are they only the fundamental conditions of (a certain kind of) Norwegian existence?

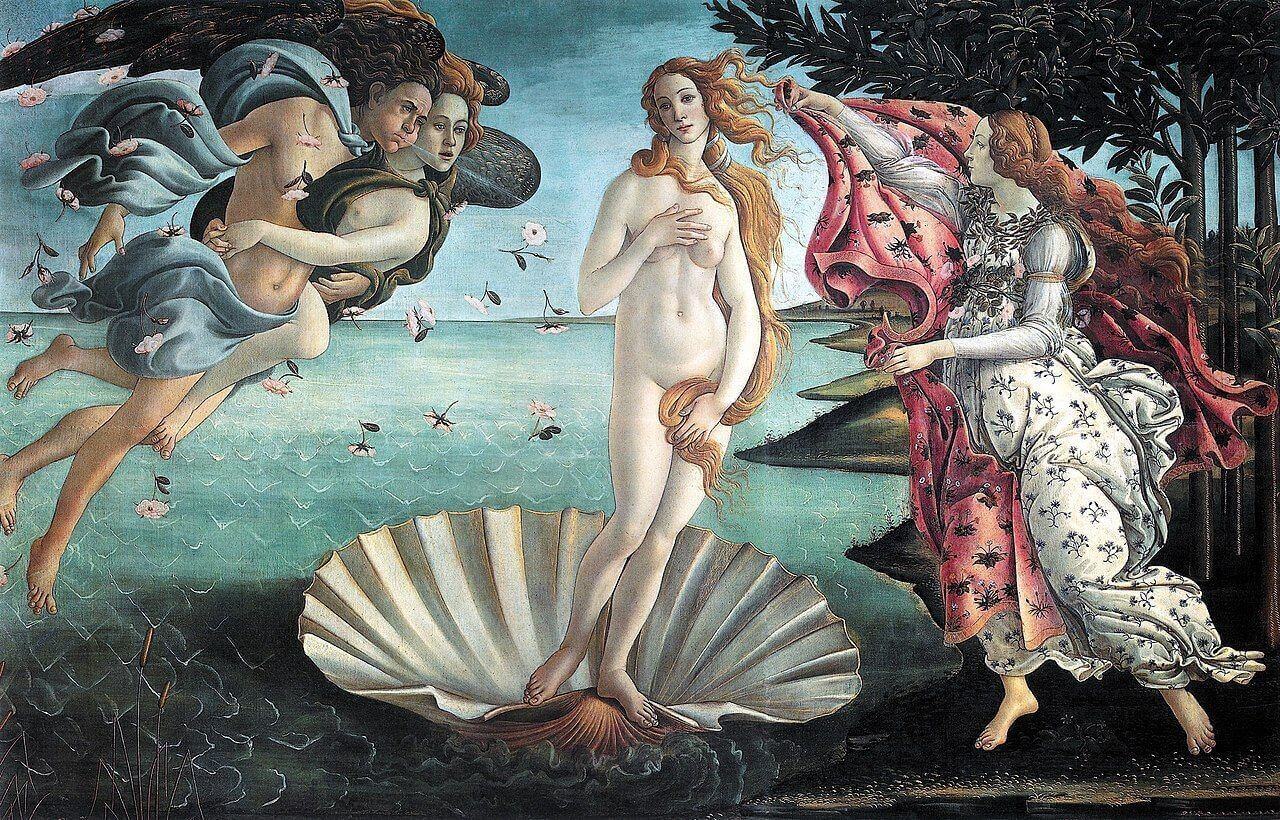

Death in the Sickroom, by Edvard Munch, 1893. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Death in the Sickroom, by Edvard Munch, 1893. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Connectedness, Vitality and Delight

I have no doubt that the Norwegian philosopher was personally preoccupied by these questions. It seemed to me that these questions were not just woven deeply throughout his talk, but also throughout his life: they mattered to him, not just as a philosopher but also as a human being. They were part of the warp and weft of his being.

Not only this, but these preoccupations seemed to be ones that the philosopher shared with at least a sizeable chunk of the audience. During the question and answer session, the other philosophers in the room asked lots of deep questions about loneliness, mortality and terror, but they seemed to take for granted the claim that these things were fundamental to human life.

What I was less convinced by was the claim that these questions were somehow fundamental. It’s no doubt true that loneliness is a part of most lives. But so too is connectedness. Is existential loneliness any deeper than existential connectedness? It’s not certain that it is. Similarly, death is something we all face (even if, as the Epicureans pointed out, we don’t experience our own death). But living is something we’re all involved in as well. It’s pretty much a full-time job. So is our mortality any more fundamental than our ongoing vitality? And as for the terror of existence, there are many terrors in the world. But there are many things of wonder and delight. So what about our experience of these wonders, these delights? Aren’t these a part of the story as well? And who is to say that they are less fundamental than terror?

On What is Fundamental

Here, the temptation might be to take one of two approaches. One is to double-down and defend the claims that these things are fundamental. The other is to strike through the words “loneliness,” “morality” and “terror,” and replace them with the words, “connectedness,” “vitality” and “delight.” Then we could set about promoting this new list as a list of what is truly fundamental.

But does this get us very far? Or does the problem go deeper than this? Perhaps the problem is in the idea that we can identify certain preoccupations or perspectives or ideas as fundamental, or more fundamental than all others. It is an undeniably common move among philosophers: the tendency to take what are legitimate preoccupations, and to give these preoccupations more weight by claiming that they are somehow fundamental preoccupations. But this move also makes conversations about what is interesting in life somewhat difficult. If you turn up somewhere with your own bundle of preoccupations, and with the conviction that these preoccupations are somehow fundamental, and somebody else rocks up with their own preoccupations, claiming they are equally fundamental, the conversation is going to be hard-going. They will tell you that you can’t talk about your preoccupations until you address their preoccupations. Meanwhile, you will argue precisely the opposite. And if you are equally matched in stubbornness, you will end up having a fruitless and ultimately boring discussion which will get you precisely nowhere.

There are, however, better ways of dealing with this. One is to treat what is going on in the way that an anthropologist might (and hope that the other person is going to extend you the same courtesy). In other words, you can think, “Oh, look, here’s a strange and uniquely quirky human being (as we are all strange and uniquely quirky human beings),” and you can resolve to hang out with them a bit more, try and get along with them, and try and find out how their world works or how it looks. This involves taking both your own preoccupations, and the other person’s, as legitimate and interesting, but being sceptical about how fundamental they really are (even if they feel like they are). And this is a way to having more fun and interesting conversations.

Of course, this isn’t always possible. The other person may not play along, leaving you with only one choice: between a conversation both boring and fruitless, on the one hand, and no conversation at all. In such circumstances, it is not unreasonable to shrug your shoulders, politely take your leave, and go and talk to somebody else.

On Failing to Worry About God and Death

This tendency to think that or own preoccupations are fundamental, and other people’s preoccupations are less so, is one of the reasons that it can be both unsettling and enriching to find yourself exposed to unfamiliar philosophical traditions. Because apparently fundamental questions are always fundamental questions within a particular cultural and historical framework. And when that framework shifts, so do the questions.

Take God, for example. In what is called, for want of a better term, Western philosophy, the question of how we demonstrate the existence of God is big news. Pick up any introduction to Western philosophy, and there’s likely to be at least one chapter (even if it is inserted only apologetically, towards the end) about God. And for many philosophers down the ages, questions about God have certainly been included among the list of fundamental questions that philosophy should and must tackle. But these questions are really not particularly big news at all in the philosophical traditions of Confucianism. When Confucius was asked about gods and spirits, he typically deflected the conversation. Why ask about gods and spirits, he would say, if you are not even capable of managing your relationships with your fellow human beings? This isn’t to say that Confucius was some kind of atheist, because to be an atheist, you need a well-formed notion of god to refute: and this is precisely what Confucius (and his cultural setting) lacked, something he had no interest in. Questions about either demonstrating or disproving the existence of gods and spirits (let alone trying to work out their attributes) not only never interested Confucius, but perhaps never entered his mind as interesting philosophical questions.

In this same passage where Confucius shrugs off talk about gods and spirits, he also takes a similarly cavalier approach to another apparently big philosophical issue: the issue of death. When asked about death, Confucius replied, “You don’t yet know life; so how can you know about death?” And he left it at that. This is a part of a more overarching insouciance in the face of death. According to the Analects, the Duke of Shu once asked Confucius’s disciple Zilu to describe his teacher. Zilu was at a loss for words. “But why didn’t you just say this,” Confucius asked. “That I am simply a person—one so full of passion he forgets to eat, one so joyful that he forgets his worries, one who does not think about old age as it approaches?”

Here, there is no tremor of existential terror in the face of mortality. The ideal way of facing death, it seems, is with a shrugging unconcern. This isn’t to say that Confucius is a philosopher who ignores death. Instead, he thinks that the really interesting question isn’t how we get to grips with the horror of our morality (there is no sign of this horror in Confucius), but instead how we deal with the deaths of others, and what it means to care for the dead. When asked about the dead, Confucius said, “Should a friend die, with nobody to care for them, I would bury them.”

If death does present a big philosophical issue for Confucius (and for later Confucians like Xunzi), the big issue is how we should care for the dead and dying, and how we should mourn, so that we can better care for the living. When his dear friend Yan Hui died, Confucius mourned so bitterly his disciples reprimand him. But Confucius replied, “If I am not to mourn for this man, then for whom?”

So it wouldn’t be quite accurate to say that death is a complete non-problem for Confucius. But if death does present us with problems, these are not the same kind of problems as those that preoccupy Norwegian philosophers.

Constellations of Thought

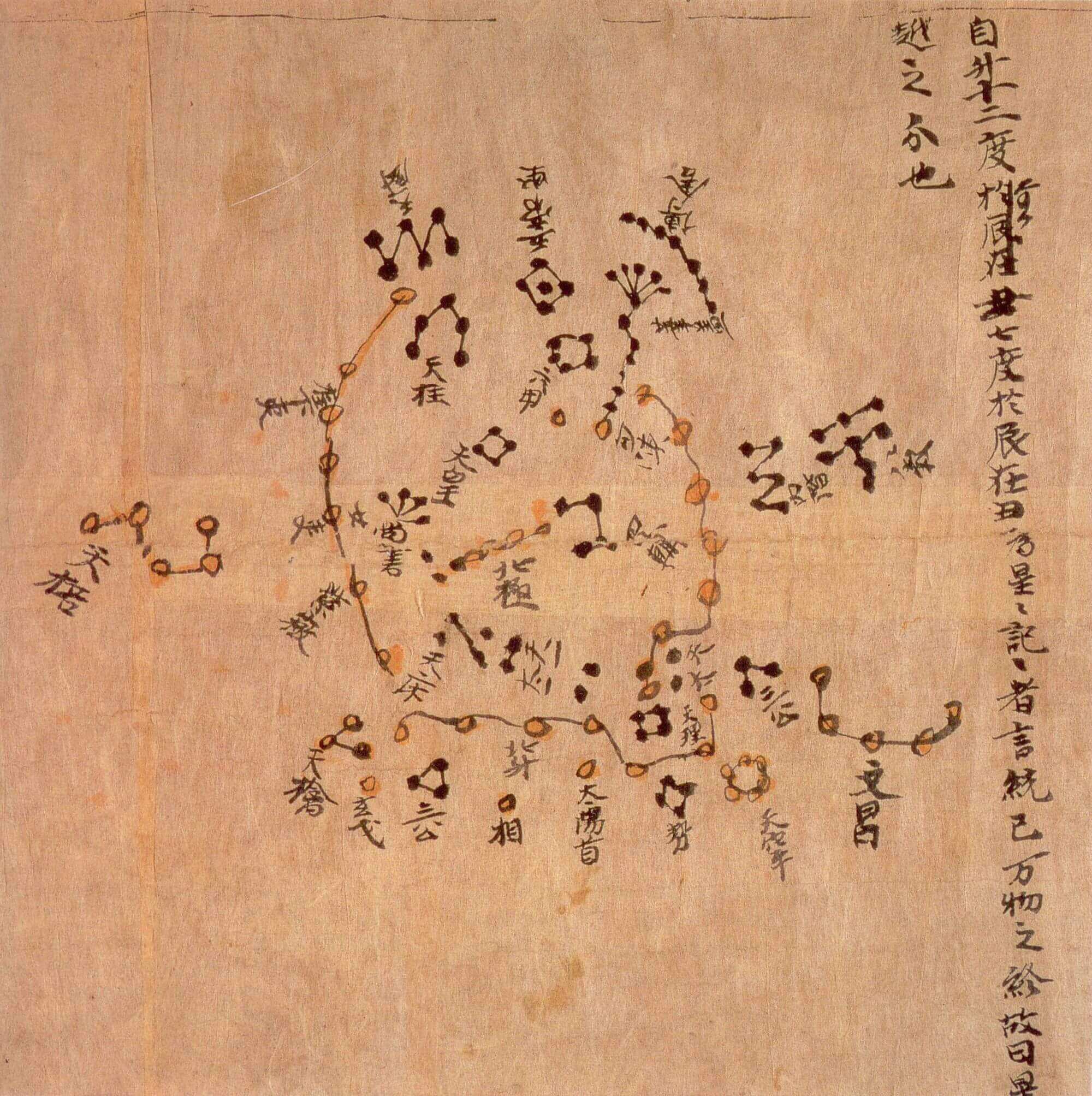

Dunhuang Star Map, British Library. Tang Dynasty. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Dunhuang Star Map, British Library. Tang Dynasty. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

It is, of course, possible to say that Confucius was misguided. We could claim that he didn’t recognise the importance of questions about God, or about death (or about other big issues, like Free Will… but we’ve not got space to open that can of worms!), and that this was a philosophical error. We could say that in comprehensively failing to recognise these kinds of questions as fundamental, Confucius was simply a bad philosopher. But it’s not clear that this teaches us anything new about Confucius’s preoccupations, or about our own preoccupations, or about human life in general. Conversely, we could dig in and claim that Confucius’s concerns are the real, true fundamental concerns, and that everybody else (from Saint Augustine to Norwegian philosophers) is wrong or misguided. But again, this doesn’t get us very far.

Instead, it is more useful to go back to that more anthropological approach, and to think in terms of constellations of thought, each of which cluster around specific sets of concerns and preoccupations. These concerns and preoccupations may be (as is the way with constellations) contingent and to some extent arbitrary: they are the result of particular histories and particular sets of conditions. But they are no less compelling for all that.

This is one reason that it is worth reading across and between philosophical traditions. Because the more you read across different philosophical traditions, the more it becomes apparent that in these traditions, the maps of preoccupations are very different from each other. What is a problem in one place is often a non-problem somewhere else. And vice versa.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t many points of connection: there are issues and tensions that recur throughout our lives, simply by virtue of being human: pre-philosophical facts we can’t get round. It’s a fact that we all die. It’s a fact that we need to eat and find shelter to survive. It’s a fact that we are social animals. But the meanings we give to death, or our need for nourishment and shelter, or our social existence, are not the same across contexts. There is no one map for human life. And thinking there should be a single map, or a set of fundamental truths, is going to cramp our style and diminish our creativity.

This, finally, is one reason why here at Looking for Wisdom, we care about exploring a rich diversity of philosophical traditions. Because in doing so, we can free ourselves from asking the same questions we have always asked, and we can find ways to start creatively drawing new maps of human life.