Philosophy in times of strife

The Chinese Legalist philosopher Han Fei (韓非) (281-233 BCE) was born a member of the royal household in the small state of Han. What we know about Han Fei comes from the unreliable Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian. The stories may not be entirely trustworthy, but we do know that the context of Han Fei’s life was one of the political strife that marked the centuries known in China as the Warring States period (dating from 476 to 221 BCE).

Han Fei studied with the Confucian philosopher Xunzi, who argued that human nature was crooked and in need of correction. There was ample evidence for this view in the brutal political context of Han Fei’s day. But Han Fei’s thinking departed from that of his teacher. Where Xunzi emphasised the role of ritual in correcting our wayward natures, for Han Fei, the main instrument of correction was law: the apportioning of punishments and rewards.

Like many philosophers of his day, Han Fei aspired to become a political advisor. But he was hampered by one problem: according to Sima Qian, Han Fei had a stutter. This was a serious impediment in the courts of his day. For political advisors, glibness and fluency were a means to getting noticed. And it was all too easy to dismiss Han Fei’s thinking on account of his difficulty in speaking.

But if Han Fei’s stutter hampered his ability to persuade the ruler of Han of the coherence of his ideas, it also gave fuel to his writing: when he could not gain the ear of the ruler of Han, he decided to write his ideas down.

The philosopher and the poison

Han Fei’s writings did not take hold in his home state. But over in neighbouring Qin, the ruler, King Zheng (later to become Qin Shihuang, the First Emperor of terracotta army fame) was impressed. When Qin launched an attack on the neighbouring state of Han, the king of Han sent Han Fei as an emissary to negotiate peace.

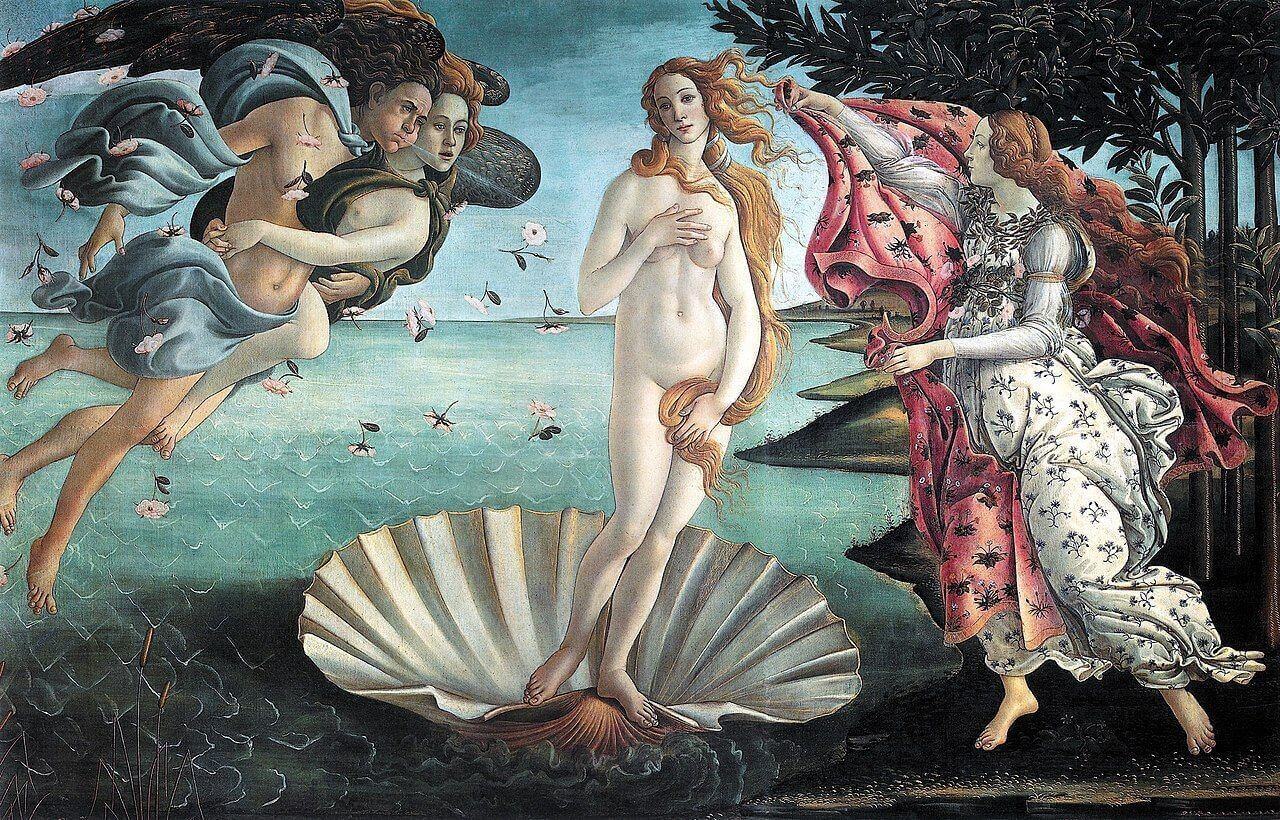

18th-century image of Qin Shihuang. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

18th-century image of Qin Shihuang. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The ruler of Qin was at first excited to welcome Han Fei into his court, and was impressed by his ideas. But there was already a philosopher-in-residence in the Qin court, a former fellow student of Xunzi’s called Li Si. Perhaps worried that his position was under threat, Li persuaded king Zheng that Han Fei could not be trusted. He had Han Fei imprisoned on trumped-up charges of double-dealing, and then promptly dispatched poison to the prison.

Knowing he had no other way out, Han Fei took the poison, thus ending his life.

Han Fei’s philosophy

The book that is attributed to Han Fei, known as the Han Feizi, (the book of Master Han Fei), was compiled by Han Fei’s disciples after his death. As with many texts from this era, the authorship has been contested, but the consensus is that at least the greater part of the Han Feizi was written by Han Fei.

Han Fei’s philosophy has multiple roots. He takes an abiding concern with human selfishness from his mentor Xunzi. He argues for the regulatory function of law, in the tradition of earlier philosophers from the tendency in Chinese philosophy known as fa jia (法家), usually translated as “Legalism.” And he takes ideas from the Daoist traditions, in particular the idea of non-doing or wu wei, but reimagines this non-doing in the context of the ruthlessness of court life.

The malleability of human nature

For Han Fei’s teacher, Xunzi, goodness is not natural, but artificial. We are bad by nature; but we make ourselves and our lives good and beautiful by crafting ourselves, the way a carpenter might bend, straighten and craft wood. There are many ways that we might do this: one is the kind of system of punishments and rewards that Han Fei also approved of; another is the use of ritual as a form of collective and individual cultivation.

However, Han Fei departs from his teacher in several respects, one of which was his insistence that the old debate about the goodness or badness (see here) of human nature was ultimately fruitless. For Han Fei, human nature is changeable and malleable: we live, he claimed, in accord with our circumstances. So the point is not to straighten out an already crooked nature. Instead, it is to put in place a framework so that this changeability of our natures can be regulated and developed.[1] And one of the best ways of doing this is by the institution of law.

Law, method, and impersonal charisma

The legalist tradition in Chinese philosophy is sometimes traced as far back as the philosopher Guan Zhong (see the link here). It is a tradition that emphasises the role of law or fa – the balance of punishments and rewards – in maintaining social order. For legalist philosophers such as Han Fei, the role of a ruler is to bring about both unity and order within the state. And the primary instrument through which the ruler does this is through putting in place a system of law that will serve to regulate human behaviour.

A system of law that is clear, unambiguous and applied rigorously has the advantage of making human behaviour systematic: it channels our wayward natures into behaving in ways that support the power and unity of the state, and it punishes those who undermine this power and unity.

But law is not sufficient for the good running of the state. Han Fei also employs two other concepts that are important within political life. The first is shu (術), which can be translated as “artfulness” or “method.” This is about how the ruler maintains their administration, to offset the danger of the power of the law being usurped. And the second is shi (勢), meaning potency or charisma.

The notion of charisma or potency in Han Fei is not about personal charisma: it is best for the people to know nothing at all about the ruler as an individual. But projecting a sense of impersonal charisma or potency helps underpin the law with a sense of unshakeable necessity.

Ruling by doing nothing

This idea of impersonal charisma may be puzzling. But here Han Fei reaches for a concept from the traditions of Daoist thought to make sense of it. And this concept is that of non-doing, or wu wei (無為).

At first glance, this might seem like the opposite of a political idea. How can one govern by non-doing? What does this mean? For Han Fei, the idea is this. A monarch who parades around looking like a monarch, who endlessly and heroically acts, becomes an easy target for their enemies. But there is something much more terrifying about a monarch who is not seen to act, who is almost invisible, and who rules with ease and confidence in accord with the inflexible law.

This is the kind of inaccessible, impersonal ruler who strikes fear in the heart of their subordinates. And this is the kind of rule that ultimately endures. At least in theory (although in practice, Qin Shihuang’s empire was short-lived).

Here is what Han Feizi says, in the translation by Burton Watson.

The ruler must not reveal his desires; for if he reveals his desires his ministers will put on the mask that pleases him. He must not reveal his will; for if he does so his ministers will show a different face. So it is said: Discard likes and dislikes and the ministers will show their true form; discard wisdom and wile and the ministers will watch their step. Hence, though the ruler is wise, he hatches no schemes from his wisdom, but causes all men to know their place. Though he has worth, he does not display it in his deeds, but observes the motives of his ministers. Though he is brave, he does not flaunt his bravery in shows of indignation, but allows his subordinates to display their valor to the full. Thus, though he discards wisdom, his rule is enlightened; though he discards worth, he achieves merit; and though he discards bravery, his state grows powerful. When the ministers stick to their posts, the hundred officials have their regular duties, and the ruler employs each according to his particular ability, this is known as the state of manifold constancy.

Hence it is said: “So still he seems to dwell nowhere at all; so empty no one can seek him out.” The enlightened ruler reposes in nonaction above, and below his ministers tremble with fear. [2]

For the Han Feizi, the effective strategy for ruling, and the most powerful source of charisma, is to be as bland as possible. It is a charisma of no charisma, an emptiness that exudes power. And what could be more terrifying than that?

Notes

[1] See Alejandro Bárcenas’s paper ‘Xunzi and Han Fei on Human Nature,’ in International Philosophical Quarterly 52:1, issue 2016 (June 2012).

[2] Burton Watson (2003), Han Feizi: Basic Writings, Columbia University Press, pp. 15-16.

Further reading

Try François Jullien’s In Praise of Blandness (Zone Books 2004), to explore the curious idea of how having no personal style, no flavour or no taste may turn out, paradoxically, to be a powerful thing!