Life

Perhaps fittingly for a philosopher who saw change as fundamental to the universe, our knowledge about Heraclitus himself is similarly changeable and hard to pin down. At various times in history, he has been referred to as the ‘weeping philosopher’ (due to his supposed pessimism), and ‘Heraclitus the Obscure.’ And this obscurity is amplified by the fact that all we have left of Heraclitus’s philosophy are scattered fragments quoted by later writers.

This mysterious philosopher was born around the year 535 BCE in Ephesus, close to Miletus (also the home town of Thales and Diotima). He is said to have written a book called On Nature, which he gave to the temple to Artemis in Ephesus for safe-keeping; but the book has not survived.

Unreliable Biographies

Later biographies of Heraclitus say that he was from a high-ranking family in Ephesus, and turned away from the opportunity of becoming king of Ephesus so he could give his attention to philosophy. The biographies say he shunned society, and had a low opinion of his fellow human beings. But none of these accounts are particularly reliable. According to the later writer Diogenes Laërtius, he was so appalled by society that he took to the hills, where he subsisted on mountain plants.

Diogenes Laërtius also tells some lurid, but unsubstantiated, stories of Heraclitus’s death, which was traditionally at the age of sixty. According to Diogenes, Heraclitus suffered from oedema, or fluid retention, and attempted to cure himself by smearing himself in cow-dung to draw out the moisture. It was whilst smeared with cow dung that he died: either through overheating after lying all day in the sun, or torn apart by dogs. The story, however, has the whiff of untruth, and like all the stories told by Diogenes Laërtius should be taken lightly.

Philosophy

It is impossible to reconstruct the whole of Heraclitus’s philosophy, and his book On Nature has not survived. But from the fragments that remain, it is possible to see Heraclitus’s distinctive vision of the world. In this vision, the world is in a state of perpetual flux, always changeable.

A Flowing World

Heraclitus’s most famous saying is ’everything flows.’ Many other fragments from Heraclitus support this idea that the world is a series of constant transformations. One recorded fragment says as follows:

It is not possible to step into the same river twice.

In other words, although we want to pin things down, and want to make sure things stay put for long enough for us to grasp hold of them, the world doesn’t work like this. It is complex and shifting.

This gets more interesting when you read another of Heraclitus’s sayings, where he makes the seemingly self-contradictory claim that:

We both step and do not step into the same rivers; we both are and are not…

What’s going on here? One answer is that even staying the same involves constant change and flux. The river remains the same river precisely because it is being constantly renewed by new water flowing down from the mountains (just as our bodies remain the same by being constantly renewed by us eating, drinking and living our lives). Permanence itself — the permanence of rivers, of ourselves, and perhaps by extension the permanence of all things — is built upon processes of change and renewal.

Fire and the Exchange of All Things

For Heraclitus, change is not just chaotic and disorderly. It takes place according to particular patterns. This leaves Heraclitus with a further question: how does change happen? How can we understand the changing, unpredictable world, whilst also seeing the orderliness of this change? And here we come to another fragment:

Everything is an exchange for fire, and fire for everything—as goods for gold, and gold for goods

One common way of reading this is by saying that for Heraclitus the underlying reality of the world is fire (just as for Thales, the underlying reality of the world was water). But if you read the passage more closely, you can see that this isn’t quite what Heraclitus is saying. Instead, he is saying that everything is an exchange for fire. And he explicitly makes an analogy with the way that gold coinage is used for trading between goods.

If we take this analogy seriously, it suggests that Heraclitus’s philosophy is more subtle than it is sometimes accused of being. The goods that were traded in the marketplace at Ephesus were not made of gold. Gold is not some kind of reality that underlies all these exchanges. Instead, gold acts as a constant measure that can regulate exchange. What money does is that it allows us to draw equivalents: this many chickens are worth this many pigs; one night at an inn is worth so many kilos of beans; seventeen seafaring vessels are worth however many sacks of wheat. The currency itself (gold, in this case) is arbitrary: it could be shells, or almost anything else. It could be something entirely abstract, a set of numbers in a database. What matters for there to be reliable, consistent exchanges like those in the marketplace of Ephesus is for there to be a common measure of exchange.

So what Heraclitus is saying (or what he may be saying because he is, after all, ‘Heraclitus the Obscure’!) is that the things of the world undergo constant change, transformation and exchange. But there is a constant measure underneath — which he calls fire — just as there is a constant measure underneath the exchanges that happen in the marketplace.

The implication is that although the world in changing and in flux, the transformations of the world are underpinned by regularity and order.

Further Reading

Books

The two go-to books on the Presocratic philosophers are The Presocratic Philosophers, by Jonathan Barnes (Routledge 1982), and Catherine Osborne’s Presocratic Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press 2004).

Online Resources

The ancient history encyclopedia has a piece on Heraclitus, contrasting his thought with that of Buddhism. See the link here.

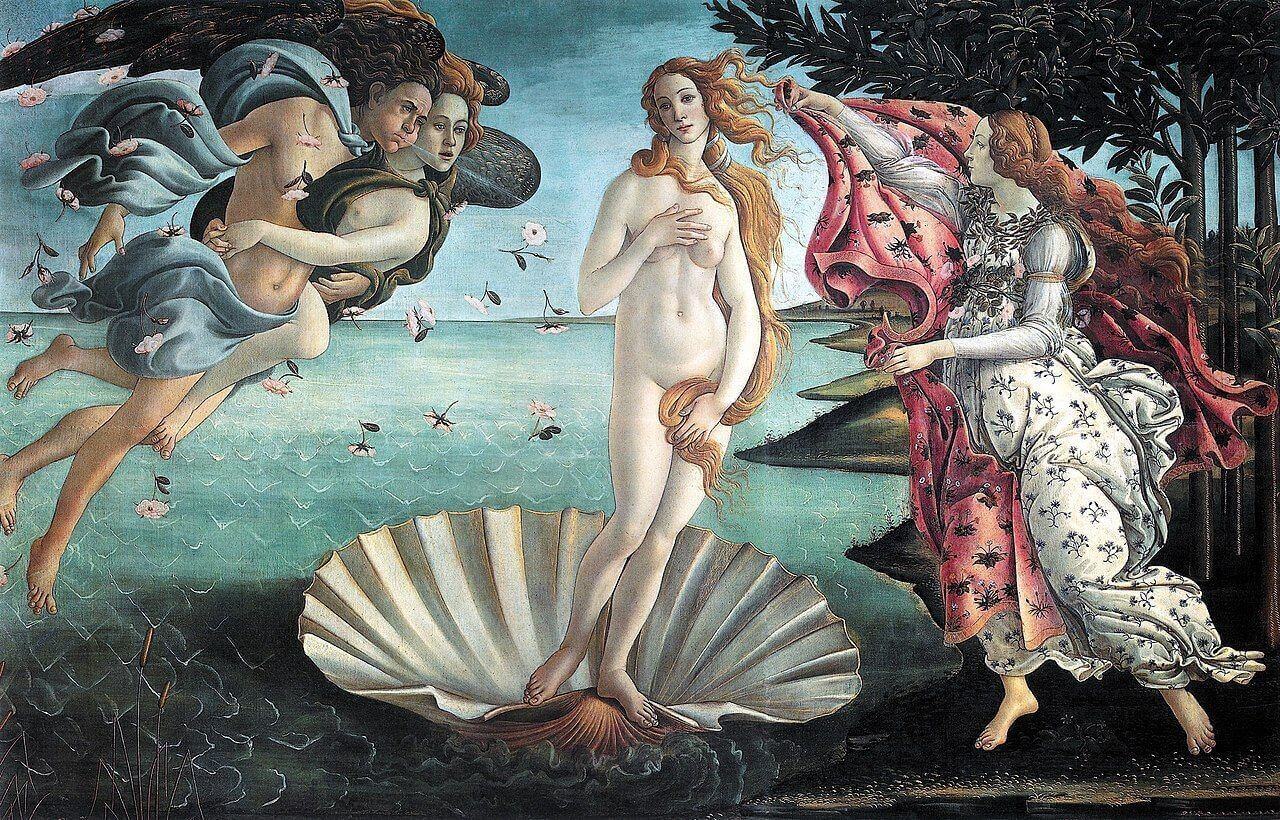

Image: Heraclitus by Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588–1629). Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.