A This-Worldly Philosophy

In popular culture, there can be a tendency to see Indian philosophical traditions as somehow inherently spiritual, and to contrast this supposedly mystical East with a rational West. But this division of the world into a rational West and a mystical East maps poorly onto the facts. Much philosophy in the West, from Plato and Socrates onwards, is tangled up with various forms of mysticism, and with a preoccupation with the divine. And throughout Asia, there are traditions of thought that are resolutely this-worldly.

In India, there has long been a robust strain of this-worldly philosophy. This philosophical tradition is usually referred to as Cārvāka. The derivation of the word is contentious, but in some accounts, it comes from a root meaning either “to chew on”, or else “sweet speech.” From around the sixth century, the Cārvāka philosophical tradition was also referred to as the Lokāyata, deriving from the expression lokeṣu āyatam, meaning widespread among the people.

The Cārvāka school traces its origins back to a set of obscure, lost texts called the Bārhaspatya sūtras, attributed to an author called Bṛhaspati. We don’t know much about the author, not least because there are no fewer than twenty-nine Bṛhaspatis in the ancient Indian tradition, so there’s lots of scope for confusion around which is which. Some accounts claim the author of these texts was none other than the sage Bṛhaspati, who was a teacher to the gods. In this version of events, Bṛhaspati taught the doctrine of materialism to deceive and bring ruin to the demons.

Whoever the author of these early materialist texts was, most of what remains of these traditions is only fragmentary, making it hard to pin down in detail what ancient Indian materialist philosophy looked like. But one of the earliest philosophers associated with the Cārvāka traditions is a character who can be found lurching occasionally into view in the religious texts of the Buddhists and the Jains, dressed in a hairy blanket.

The Man With the Hairy Blanket

Ajita Keśakambalin was a man of simple tastes. A contemporary of the Buddha, he too was a renunciant who had given up the household life in favour of the life of a wandering philosopher. His name literally means “Ajita of the Hairy Blanket”, and as far as it is possible to tell, he roamed about India wearing nothing but a blanket woven out of hair. We don’t know anything first-hand about Ajita’s philosophy, but we do know a little about how his opponents saw him.

In the Buddhist text, the Sāmaññaphala Sutta, or the Discourse on the Fruits of the Ascetic Life, we meet King Ajātasattu. The king has a problem on his hands. He has not long before imprisoned his father, Bimbisāra, ordered his torture and left him to die. Now Ajātasattu is worried about the consequences of his deeds. So he sets about interviewing the philosophers of his realm, the see if there is anyone whose teaching might bring him peace.

One of the philosophers he speaks with is Ajita. The text tells us that Ajita is already in old age, and has quite a sizeable community of followers. However, Ajita’s philosophy offers no comfort for a king in search of moral reform.

Ajita said: ‘Great king, there is no meaning in giving, sacrifice, or offerings. There’s no fruit or result of good and bad deeds. There’s no afterlife. There’s no obligation to mother and father. No beings are reborn spontaneously. And there’s no ascetic or brahmin who is well attained and practiced, and who describes the afterlife after realizing it with their own insight. This person is made up of the four primary elements. When they die, the earth in their body merges and coalesces with the main mass of earth. The water in their body merges and coalesces with the main mass of water. The fire in their body merges and coalesces with the main mass of fire. The air in their body merges and coalesces with the main mass of air. The faculties are transferred to space. Four men with a bier carry away the corpse. Their footprints show the way to the cemetery. The bones become bleached. Offerings dedicated to the gods end in ashes. Giving is a doctrine of morons. When anyone affirms a positive teaching it’s just hollow, false nonsense. Both the foolish and the astute are annihilated and destroyed when their body breaks up, and don’t exist after death.’

Came in Like a Wrecking Ball

If we are to believe the Buddhist texts, Ajita’s philosophy was almost entirely destructive. He disavowed almost every moral, philosophical and religious doctrine of his day. He argued that there was no karma, no fruit of good deeds. There was no rebirth. There was no point in making offerings and sacrifices to the gods. Ethics itself was a sham. And wisdom didn’t help you much because the wise also die. In the world of Ancient Indian philosophy, Ajita came in like a wrecking ball and messed everything up.

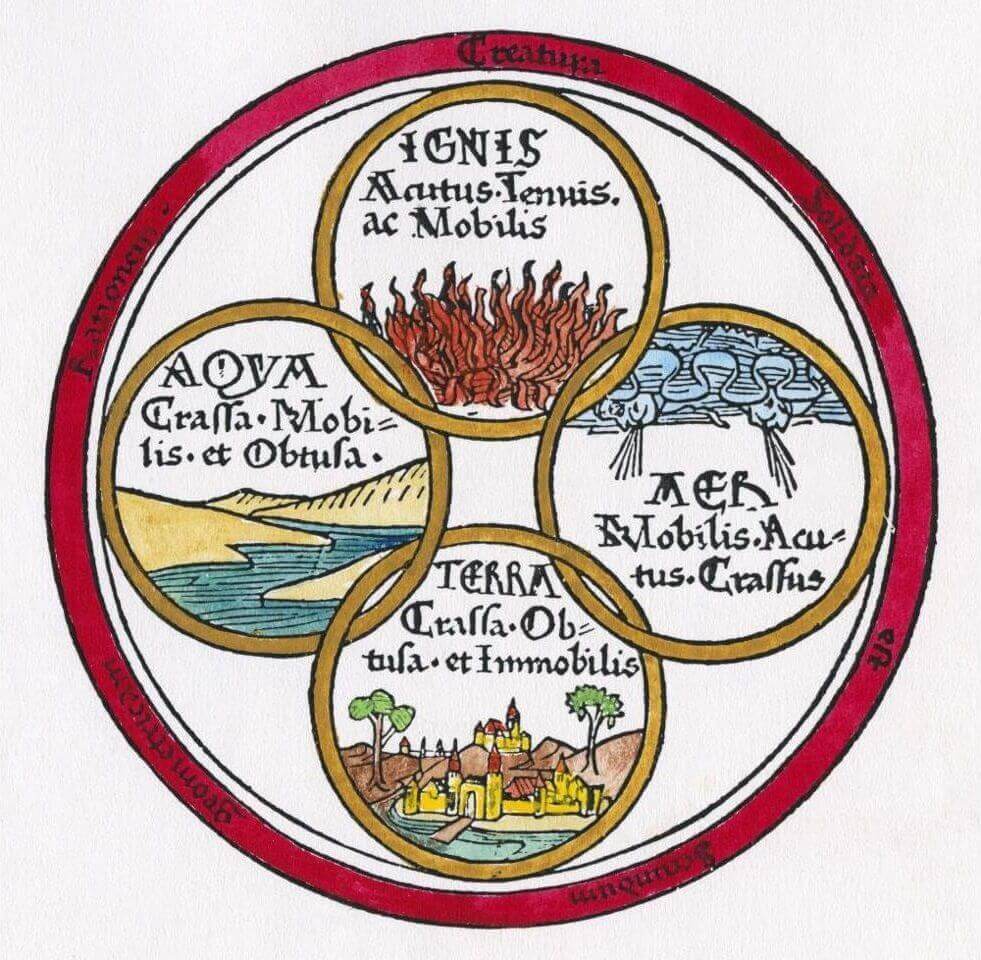

But did the Cārvāka philosophers have anything more positive to contribute? If you read the text carefully, you can see that there is a positive claim here as well. There’s a very specific assertion that we are made up of four elements that have coalesced temporarily to fashion us, and that on our death will break apart. What are we? Ajita’s answer is this: we are nothing more than earth and water, fire and air (exactly the same list of elements that appears in the work of the philosopher Empedocles in Greece). And for Ajita, even the self or the soul is nothing more than a combination of these four elements.

The four elements of Empedocles. From Lucretius De rerum natura, published by Tommaso Ferrando, Brescia, 1472. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Hedonism, Asceticism, or Something in Between?

This materialist view means that many of the ethical claims of the ancient Indian world have to be thrown out. There’s no need to fret over rebirth, because when we’re gone, we’re simply gone. We don’t need to worry about the fruits of our good and bad deeds, because the world doesn’t work like this.

But does this mean that Cārvāka philosophy didn’t have any ethics to offer at all? After all, ethics is inescapable. Even if you undermine all the traditional frameworks there are for understanding ethics, you are still left with the question: how should I live?

One answer is that we should simply grab all the pleasure that we can, while we can. The Cārvāka philosophers were often associated with hedonism, the notion that pleasure is the sole end of human life. One preserved early fragment seems to suggest this:

While life remains let a man live happily; nothing is beyond death. When once the body becomes ashes, how can it even return again? [1]

Another version of this same verse takes things even further, reading, “While life remains, let a man live happily, let him feed on ghee even though he runs into debt.”

This might seem strong evidence that the Cārvāka philosophers were committed to living it up. But the difficulty with this is that when we look at Ajita’s own mode of living, we find something that seems a long way from outright hedonism. Going around India dressed in a hairy blanket doesn’t look much like a life committed to wild, hedonistic excess.

Perhaps if the Cārvāka texts had survived, we would have more insights into the varieties of ethics they proposed. But the example of Ajita suggests that other responses than outright hedonism are possible. It is true that living happily might mean feasting on ghee until you are driven into debt. But then again, it might mean living simply, dressed in a hairy blanket, wandering where you choose, a way of life closer to that of the Cynics in Ancient Greece, than to the image of a hedonist addicted to bodily pleasure.

Notes:

[1] R. Bhattacharya’s Studies on the Cārvāka/Lokāyata (Anthem Press 2011), p. 91.

Further Reading

Books

R. Bhattacharya’s Studies on the Cārvāka/Lokāyata (Anthem Press 2011) is probably one of the best recent surveys.

There’s also the classic study Lokāyata: A Study in Ancient Indian Materialism (People’s Publishing House 1959) by Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya.

Online

This piece on the APA blog is worth reading.