Life

Far-ranging wisdom

Jing Jiang was a Chinese philosopher who was born in the state of Lu around 540 BCE. She appears in the Discourses of the States, or Guoyu, a text that dates to between the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. She is also featured in the later Biographies of Exemplary Women or Lienü Zhuang, an anthology compiled in by the scholar Liu Xiang who lived between 77 BCE and 6 BCE.

Jing Jiang was the wife of Gongfu Mubo, a high-ranking official in Lu. Predeceased by her husband, she raised their son, Gongfu Wenbo, alone. In both the Guoyu and the Lienü Zhuang, she can be found instructing her son on a wide range of matters: from ritual, to the virtues of hard work, to politics.

This instruction is not just something she does while the somewhat wayward Wenbo is growing up. Even after Wenbo has risen to become a rather hapless minister in Lu, Jing Jiang is on hand to put him right.

Wrangling Wenbo

The Biographies of Exemplary Women describes how as a young man, Wenbo leaves home to study. When he returns, he thinks he is all grown up. He hangs around with a bunch of friends, all young ruffians like himself, and all of whom look up to him because of his superior rank.

Jing Jiang realises her son is not going to make much of himself by carrying on like this, so she takes him to task. She tells him to hang out instead with those who are older and wiser, people he __ can look up to. The text continues:

After this he chose strict teachers and worthy friends to serve him. Those with whom he lived and socialized were all very elderly, toothless gentlemen with yellowed hair. Wenbo would adjust the lapels of their robes, roll up their sleeves for them, and personally serve them food. — Biographies of Exemplary Women, p. 12

Only now does Jing Jiang recognise that her son is “now a grown man.” Only now can he start to develop his the fulness of his human capacity, having apprenticed himself, in all humility, to exemplary models.

Philosophy

In one text, Confucius, China’s most famous sage, praises Jing Jiang for her knowledge of ritual and her exemplary conduct. The Biographies of Exemplary Women call her a woman who is “far-ranging in her wisdom and [who] understood the rites.”

But as the scholar Lisa Raphals has argued, Confucius’s praise only goes so far: he praises her for her knowledge, and for her ability to cultivate the qualities of her son; but he does not give her credit for her own self-cultivation. Jing Jiang may be virtuous and cultivated, but Confucius is uninterested in this. For Confucius at least, her virtue is only of interest to the extent that it impacts upon the hapless Wenbo.

Politics, weaving and gender:

Nevertheless, Jing Jiang is interesting precisely because of the force of her arguments, which are effective and carefully woven, and which find ways round the gendered expectations of her time.

The most famous example of this is the advice she gives Wenbo after he has become a minister. He is clearly doing a poor job and Jing Jiang decides to speak with him. But in the patriarchal culture of Ancient China women were not judged (by men at least) to have any expertise in politics. So this presents Jing Jiang with a problem.

To get round this problem, she starts by making an analogy: politics, she says, is like weaving. Wenbo does not contest this analogy, and he is happy to accept it as the premise of his mother’s argument.

Once Wenbo has accepted this premise, the way cleared for her Jing Jiang instruct her son in politics.

Jing Jiang is cunning. She is aware it is taken for granted within her social context that women have expertise in the art of weaving, just as it is taken for granted that men should be considered experts in the art of politics. So having made an analogy between the two, she is free to talk about politics whilst relying on her own independent sphere of expertise, which is weaving.

Weaving the net of argument

In this way, Jing Jiang starts to weave the net of her argument. She begins by arguing that the different parts of the loom and the cloth correspond to the different parts of the apparatus of the state.

When Wenbo served as minister in Lu, Jing Jiang told him, “I will tell you how the essentials of ruling a country can be found in [the art of weaving]: everything depends upon the warp! The selvage is the means by which the crooked is made straight. It must be strong. The selvage can therefore be thought of as the general. The reed is the means by which one makes uniform what is irregular and brings into line the unruly. Therefore the reed can be thought of as the director […]"— Biographies of Exemplary Women p. 13, translation modified.

The character for “warp” is jing (經). It can also mean a standard or a rule. By the time the biographies of Jing Jiang were written, it was also the character used to refer to the classic texts that formed the core of Confucian learning. In other words, when it comes to statecraft, everything depends on the warp: on regularity, on standards, and on learning.

As her argument proceeds, Jing Jiang sets out the requirements of effective government. A state needs regularity and structure: politics is about keeping the warp and weft of society in order. But effective government also depends upon a well-made loom. In other words, an effective political system is one where all the parts perform their correct functions, and where the ministers and officials are reliable and upright.

At the end of the argument, Wenbo now understands more about politics than before. The passage ends with him acknowledging his mother’s superior knowledge.

Wenbo bowed twice and received her teaching.— (ibid.)

Weaving as political philosophy

The story in the Biographies of Exemplary Women acknowledges Jing Jiang as a knowledgable and competent advisor in what was, in Ancient China, the traditionally male domain of politics.

But what makes the story of Jing Jiang even more fascinating is the skill with which she weaves her argument. She systematically uses the analogy between weaving and politics to illuminate some important and salient features of good government. It is interesting here to compare Jing Jiang with Gārgī Vācaknavī in India, who also used metaphors of weaving to gain authority in philosophical debate.

Finally, the approach she takes to weaving her arguments shows that Jing Jiang has a clear grasp on the problems faced in a patriarchal society by women thinkers seeking to contribute to philosophical debate. And she has the skill in rhetoric and debate to see the analogy through, and press her point home.

Taken together, these things make her a political philosopher to be reckoned with.

Further Reading

Books

You can read the Lienü zhuan of Liu Xiang in Anne Behnke Kinney’s translation, Exemplary Women of Early China (Columbia University Press, 2014)

If you can get hold of it, try ‘A Woman Who Understood the Rites’ by Lisa Raphals, in Bryan van Norden’s Confucius and the Analects: New Essays (Oxford University Press 2002).

Again, if you can get hold of it, try ‘Arguments by Women in Early Chinese Texts’, also by Lisa Raphals, published in Nan Nü volume 3, issue 2 (2001), pp. 157-195. I’ve relied heavily on both of Raphals’s papers when researching this Philosopher File.

Online Resources

For more context, try the article on Women in Ancient China from the Ancient History Encyclopedia.

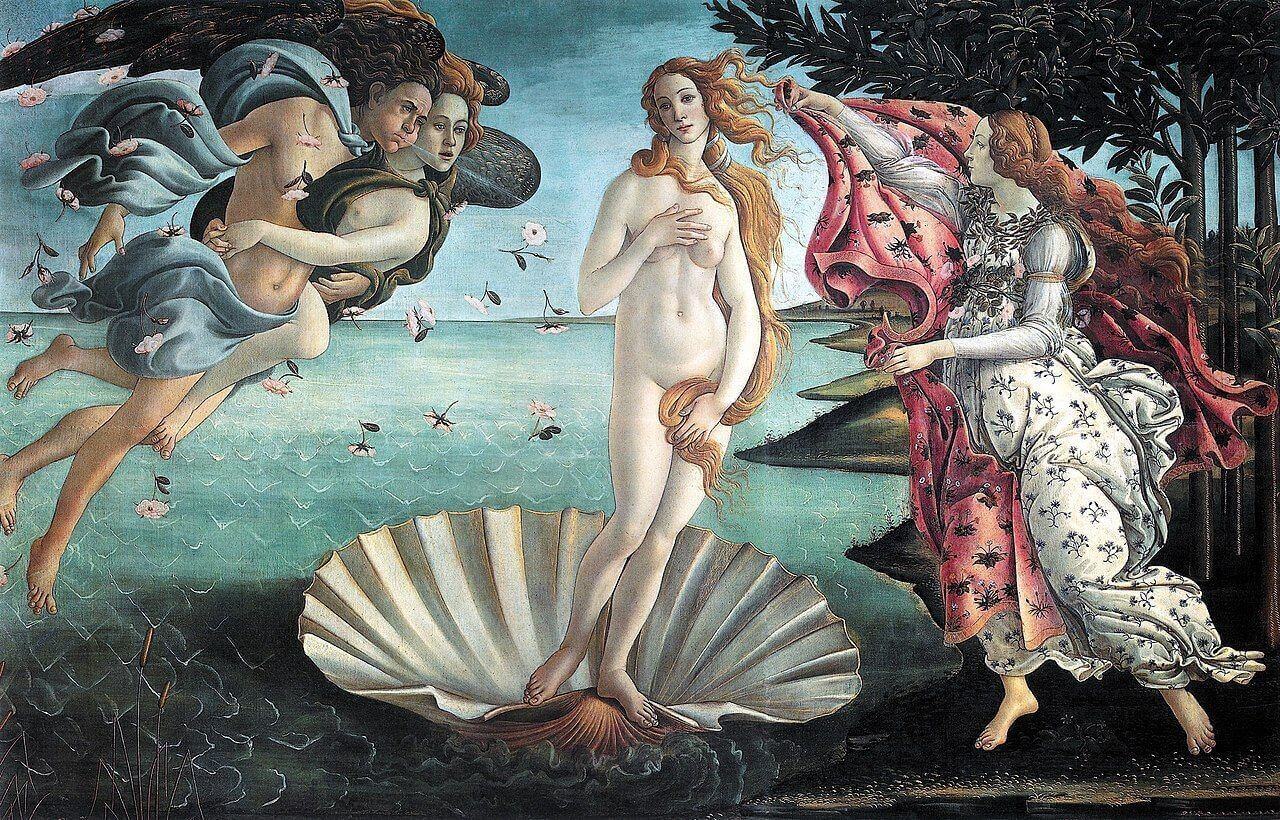

Image: Woman with Shuttle, by Zhang Lin, before 1529. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.