A complicated business…

Of all areas of human life, sex is one of the most complicated. It is the place where biology, culture, ideas of the good life and weighty moral claims collide. Questions about sex are one of the great human preoccupations. Questions like: How much sex should we have? Should we have as much as possible? Or—like the Buddhist monks, wary of desire—should we choose to abstain? Whom should we have sex with? Just ourselves? With just one other person, a life-partner or spouse? With a succession of short-term partners? With a range of people, by mutual consent and agreement? With anybody who is up for it? And, for that matter, who shouldn’t we have sex with? Then there are questions about when we should (or shouldn’t) have sex, and how we should (or shouldn’t) have it.

There’s probably no culture on earth that hasn’t developed cultures of sex—often of baroque complexity—to try and manage all this. And even if none of these questions—the question “how much?”, the question “whom?”, the question “when?” and the question “how?”—are directly philosophical questions, they all harbour deeper philosophical issues that go to the heart of how we understand ourselves, each other, what society is or could be, and what it means to be human.

But where do you even start with untangling all of this? In this week’s article, we’re going to start by asking some questions about our underlying biology. Then we’ll ask some questions about sexual ethics. And finally, we’ll ask about the problems caused by the gender imbalance of the philosophical traditions that have come down to us, and how the philosophy of sex and desire needs to think beyond the constraints of this tradition to address the questions that are at stake.

You and me baby ain’t nothin’ but mammals…

But let’s start by going back to questions of biology. Given the sheer cultural complexity of sex, this seems a not unreasonable starting point. In the first week of this series, we saw how philosopher Carrie Jenkins describes love as “ancient biological machinery embodying a modern social role.”[1] So if we go back to our underlying biological machinery, perhaps here we might find a base-level simplicity that can help us anchor all the complexity.

So, we’re going to start by putting to one side the complex questions of social roles and the part played by culture in organising our desires and our sexual lives. And we’re going to go back to biology to see how human sexual desire plays out in ways that are continuous with the way sexual desire plays out elsewhere in the animal kingdom. Because, as the Bloodhound Gang once put it, “You and me baby ain’t nothin’ but mammals / So let’s do it like they do on the Discovery Channel.”

Noah’s Ark, oil on canvas painting by Edward Hicks, 1846 Philadelphia Museum of Art. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Noah’s Ark, oil on canvas painting by Edward Hicks, 1846 Philadelphia Museum of Art. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But if we hope that this return to biology would return us to a simpler, even more innocent, view of what it means to be a sexual being, it is likely that we will be disappointed. Although some moralists might like to imagine the animal world as a place of sexual good order—with the animals going into the ark two-by-two—the reality is starkly different. The more we get to know about how sexual desire plays out in the rest of the animal kingdom, the more it becomes clear that sexual desire and sexual pleasure are complex almost everywhere, not just among human beings.

Procreation or recreation?

Among human beings, sex is both procreation and recreation: mostly the latter, occasionally the former. And it is easy to imagine that recreational sex aligns with culture, while procreational sex is about nature and is a matter of our biology. After all, we’re evolved to pass on our genes, and sex is evolution’s way of gene-mixing (see this nice overview of the evolutionary costs and benefits of sex). This tendency to separate sex as a means of procreation and sex as a means of recreation often aligns with a broader narrative that divides off nature and culture.

In the Christian philosophical tradition, there has been a long-standing claim that procreation is the natural function of sex. This makes sex as recreation morally problematic, particularly when it comes unstuck from the context of its procreative function—hence the idea that homosexuality, masturbation and other non-procreative forms of sex are morally problematic.

The medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) argued that sexual pleasure in itself was not evil, but the pursuit of sexual pleasure as an end in itself, or for its own sake, was morally problematic. The only legitimate expression of sexual pleasure, Aquinas argued, was when it took place in the context of a married relationship, with the knowledge that the natural purpose of sex is procreation:

Now just as the preservation of the bodily nature of one individual is a true good, so, too, is the preservation of the nature of the human species a very great good. And just as the use of food is directed to the preservation of life in the individual, so is the use of venereal acts directed to the preservation of the whole human race. Hence Augustine says (De Bono Conjug. xvi): “What food is to a man’s well being, such is sexual intercourse to the welfare of the whole human race.” Wherefore just as the use of food can be without sin, if it be taken in due manner and order, as required for the welfare of the body, so also the use of venereal acts can be without sin, provided they be performed in due manner and order, in keeping with the end of human procreation. [2]

But appeals to the natural function of sex as a form of procreation obscure the fact that in the rest of the animal kingdom, sex is often just as much about recreation.

In his wonderful book Pleasurable Kingdom, Jonathan Balcombe writes about the sexual exuberance of the animal kingdom. Many animals have been observed having sex in ways that have no chance of producing offspring: from collared peccaries to warthogs, and from koalas to chaffinches. Oral sex is seen across the animal kingdom. Masturbation is common in mammals, among males and females equally. It has even been observed in birds. Homosexuality is common too. Male giraffes literally neck, twining their necks around each other as they bring each other to orgasm. And as for alternative family units, among certain species of gulls, it is not uncommon for female couples to raise chicks together, while the wayward father acts just as a sperm donor. Meanwhile, creatures as varied as dolphins, herons, and swallows have been observed to have orgies (though not all together, all at the same time), engaging in group sex for fun. And inter-species sexual activity is far from unheard-of—a recent example being the liaisons between macaques and sika deer in Japan. And so it goes on. As Balcombe writes:

When we look closely we find that the animal kingdom is a sexy place, where carnality finds expression in many forms. Animals are neither priggish nor especially shy. We need only watch patiently, and try not to blush. [3]

And this is why the increasing amount of data on the sexual exuberance of the rest of the animal kingdom are so important. These data show us how the tendency to divide human sexual practices into “natural” and “unnatural” is a poor foundation for thinking through human sexual ethics. Here as elsewhere, using what we deem to be natural as a criterion for what is ethical is an unpromising line of approach.

The ethics of desire

The philosophy of sex is as complex and sprawling as human sexuality itself. And although this philosophy is not reducible to ethical questions, nevertheless, when we talk about sex it is often questions of ethics that are at the forefront. We are deeply preoccupied with questions of how we should manage what it is to be a sexual being (or—because it’s much more fun to subject others to ethical scrutiny than it is to do the same to ourselves—how other people should manage what it is to be a sexual being). This is not surprising. From one point of view, sexual desire seems to bring in its wake all kinds of individual and social harms and sufferings. From another point of view, it brings immense pleasure and can seem to be a source of creativity.

For some thinkers—for example, Saint Augustine (354-430) in the Christian tradition, and the Buddha in the Indian tradition—sexual desire is almost always morally problematic. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), the least sexy of philosophers, claims that sex is an issue because it turns the object of our desires into precisely that: an object. Kant writes, with unusual pungency, that:

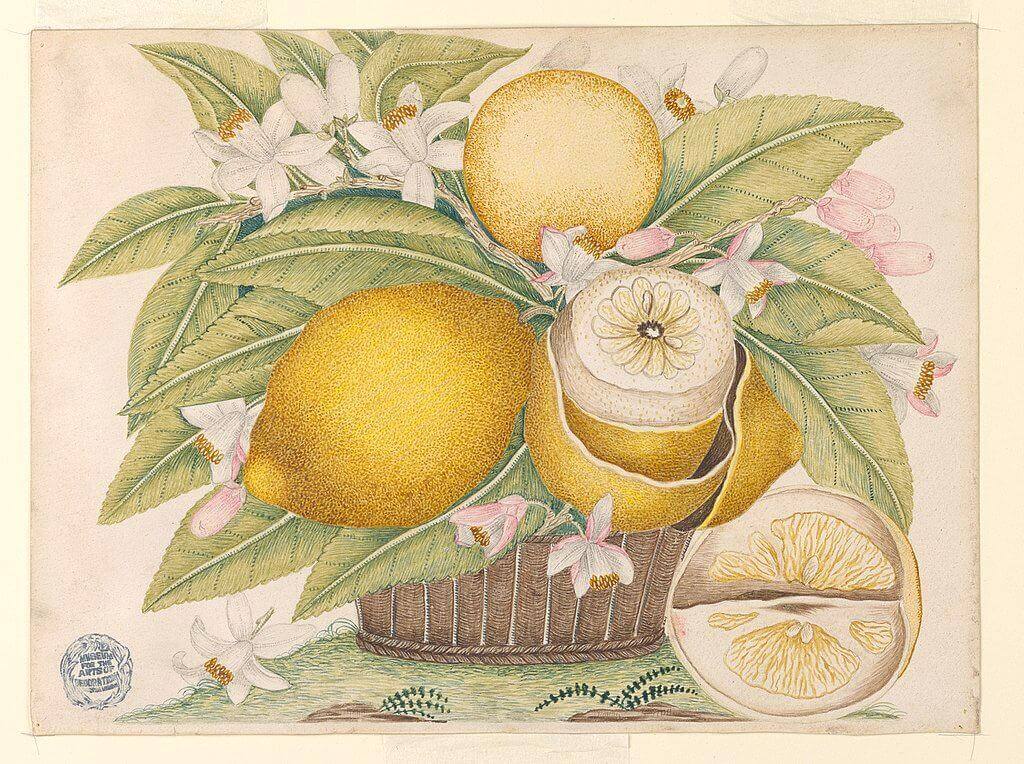

In loving from sexual inclination, they make the person into an object of their appetite. As soon as the person is possessed, and the appetite sated, they are thrown away, as one throws away a lemon after sucking the juice from it. [4]

Drawing, Lemons and Lemon Blossoms in a Basket, 18th century. Unknown artist. From the Smithsonian Design Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Drawing, Lemons and Lemon Blossoms in a Basket, 18th century. Unknown artist. From the Smithsonian Design Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Against this view, some philosophers have argued that sex is potentially creative: not just procreative, but itself a creative act. It creates pleasure. It forges social bonds (with us as elsewhere in the animal kingdom). And it opens us up to new experiences. The 2nd-century Indian text, the Kama Sutra, has this to say about kama, or desire.

Kama is the mind’s inclination towards objects which a person’s senses of hearing, touch, sight, taste and smell find congenial. Its principal element is a delightful, creative feeling pervaded by sensual pleasure and derived in particular from the sense of touch. [5]

So perhaps instead of asking whether sexual desire and sexual activity are themselves morally good or bad, it might be more helpful to ask about the ethics of how these things play out within human life, so we can harness what creative potential sex might have in human life while avoiding as far as possible the harms that it may bring.

Rethinking love and sex

And here there’s a good argument to be made for broadening out the philosophical tradition. Most of the philosophical traditions that have come down to us are marked by a substantial gender imbalance. Even when, in Plato’s dialogues on love in the Symposium, the woman philosopher Diotima is cited, she is only mentioned second-hand, her ideas channelled through the storytelling of Socrates. And many of the male philosophers throughout the tradition are preoccupied exclusively with male sexual desire and male sexual activity. Even when they claim to be talking more broadly, the absence of women’s voices means that the account they are giving is only partial. As bell hooks writes in her brilliant All About Love:

Earlier in my life, I read books about love and never thought about the gender of the writer. Eager to understand what we mean when we speak of love, I did not really consider the extent to which gender shaped a writer’s perspective. It was only when I began to think seriously about the subject of love and to write about it that I pondered whether women do this differently from men. [6]

More recently, there has been a substantial amount of philosophical work by women philosophers that aims to redress this balance because if we are going to think about love and sex and what they mean philosophically, we need to account for the whole breadth of human experience.

So perhaps I should end with Carrie Jenkins, and her book What Love Is and What it Could Be, which argues for the potentially revolutionary effects of allowing in a wider range of voices, and exploring more diverse ways of managing our sexual, romantic and personal lives. “Nonconformity can change the world,” Jenkins writes.[7] And so Jenkins argues that if we want to change things, then the onus is on us to “choose our own adventure,” to think more deeply and more responsibly about sex, to be more honest with ourselves and each other, to reduce the harms that sex can cause, and meanwhile to harness as much creativity as we possibly can.

Discussion Questions

- Are there any circumstances in which, in relation to sex, the division between what is natural and what is unnatural makes sense?

- How much do you think our increasing knowledge of what I’ve called the “sexual exuberance” of the rest of the animal kingdom should influence our ideas of human nature, particularly in relation to sex? Or is there something about human distinctiveness that makes this data less than relevant?

- Is Kant right about objectification? And if so, is objectification always bad? (See this song by Jeffrey Lewis and the Junkyard).

- In what ways is sexual desire creative? In what ways is it harmful?

Notes

[1] Carrie Jenkins, What Love Is and What it Could Be (Basic Books 2017).

[2] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae II-II, 153, 2. See the link here.

[2] Jonathan Balcombe, Pleasurable Kingdom (Macmillan 2006), p. 124

[4] Immanuel Kant, edited by Peter Heath and J.B. Schneewind, Lectures on Ethics (Cambridge University Press 1997), p. 156

[5] A. N. D. Haksar (translator), Kama Sutra (Penguin Classics 2011), p. 24.

[6] bell hooks, All About Love (William Morrow 2000), p. 9.

[7] Carrie Jenkins, What Love Is and What it Could Be (Basic Books 2017), p. 83

Further resources

Books and music

Raja Halwani’s Philosophy of Love, Sex and Marriage (Routledge 2018) is a good, thoughtful overview.

For a more challenging read, try Patricia Marino’s Philosophy of Sex and Love: An Opinionated Introduction (Routledge 2019).

And this week’s song is You Sexy Thing by Hot Chocolate.

Image: Nepalese erotic manuscript. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)