The Philosopher and the Love Potion

If you were to trust Saint Jerome – and you probably shouldn’t – the philosopher and poet Titus Lucretius Carus, better known simply as Lucretius, met an unfortunate end. The philosopher-poet was born some time after 100 BCE, a Roman citizen, and he became a follower of the atomism of Democritus and the materialist teachings of Epicurus, who emphasised the role of pleasure in human life. Lucretius died in his forties, leaving only one work behind: his great poetic treatise called On the Nature of the Universe (De Rerum Natura). Other than this, we know almost nothing about him.

But where the historical record is silent, Jerome happily steps in to provide some lurid tales of his own. According to Jerome, Lucretius drank a love potion that sent him mad. In brief moments of lucidity during his madness, Jerome tells us, Lucretius scribbled down his masterwork. And then, when he was done, he committed suicide.

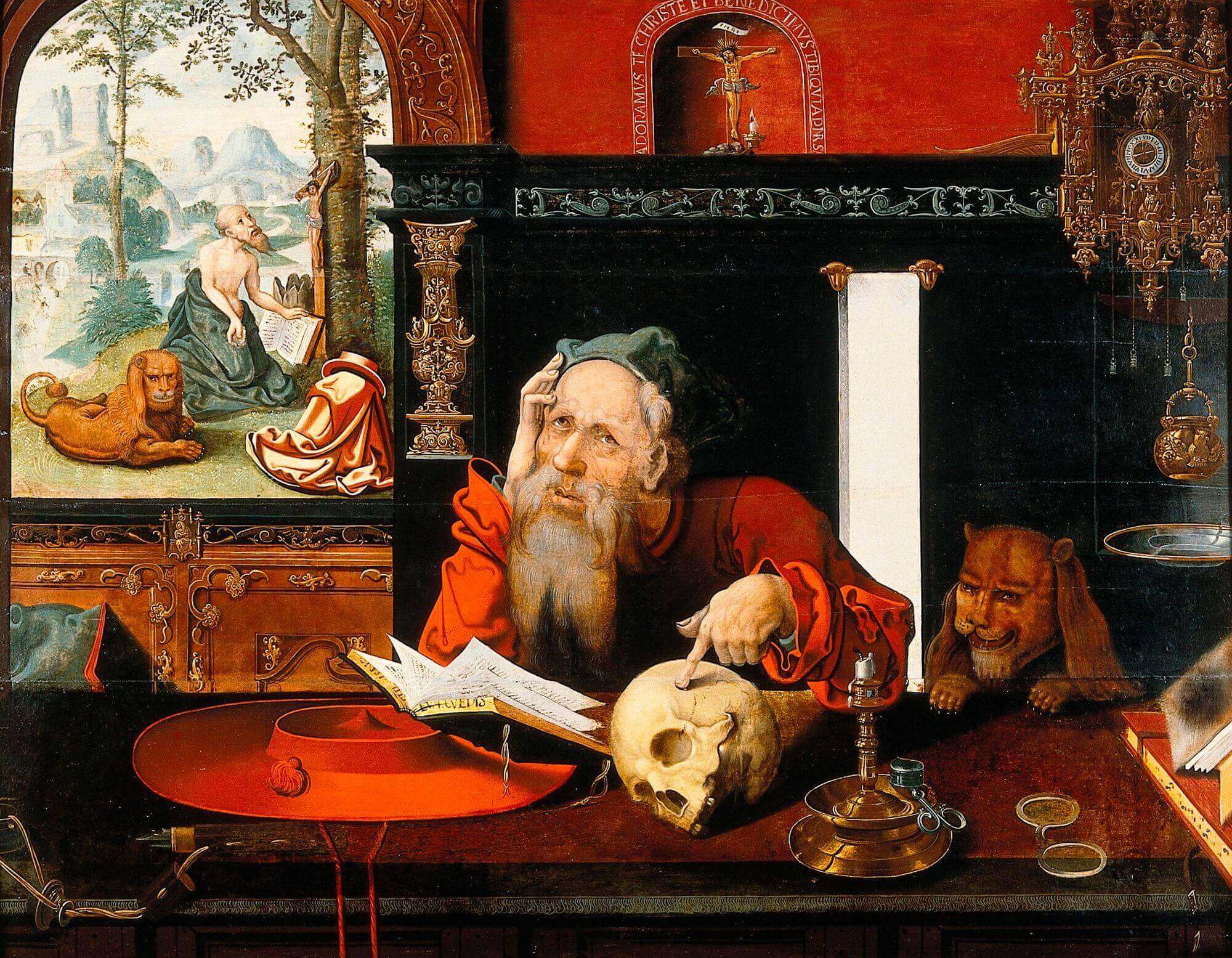

Saint Jerome in his study, thinking up mean things to say about Lucretius, while his lion (right) looks on. Public domain via Wellcome Collection.

Saint Jerome in his study, thinking up mean things to say about Lucretius, while his lion (right) looks on. Public domain via Wellcome Collection.

Honey on the Cup

This story says more about Saint Jerome than about Lucretius himself. Because for Jerome, and for many later Christian writers, Lucretius’s decidedly this-worldly, materialistic philosophy of pleasure was pretty much the opposite of all their faith stood for.

Jerome’s scurrilous little tale is supposed to make us to imagine Lucretius as having both taken leave of his senses, and been overwhelmed by an unseemly passion. One reason that Jerome was so sternly disapproving was because of the particular charm of Lucretius’s writing. As a philosopher, Lucretius is seductive, in a way few philosophers are. He writes not in prose, but in verse. And although the vision he sets out of the universe is challenging, the way in which he presents it draws the reader in, sweetening the bitterness of philosophy with poetry. In On the Nature of the Universe, Lucretius explains his rationale like this (in the translation by Alicia Stallings).

Consider a physician with a child who will not sip A disgusting dose of wormwood: first, he coats the goblet’s lip All round with honey’s sweet blond stickiness, that way to lure Gullible youth to taste it, and to drain the bitter cure, The child’s duped but not cheated – rather, put back in the pink – That’s what I do. Since those who’ve never tasted of it think This philosophy’s a bitter pill to swallow, and the throng Recoils, I wished to coat this physic in mellifluous song, To kiss it, as it were, with the sweet honey of the Muse. That is the purpose of my poetry, as you peruse My lines, to try to keep your mind’s attention, while you start To understand the framework at the universe’s heart. (936-950).

Atoms, Void and Swerve

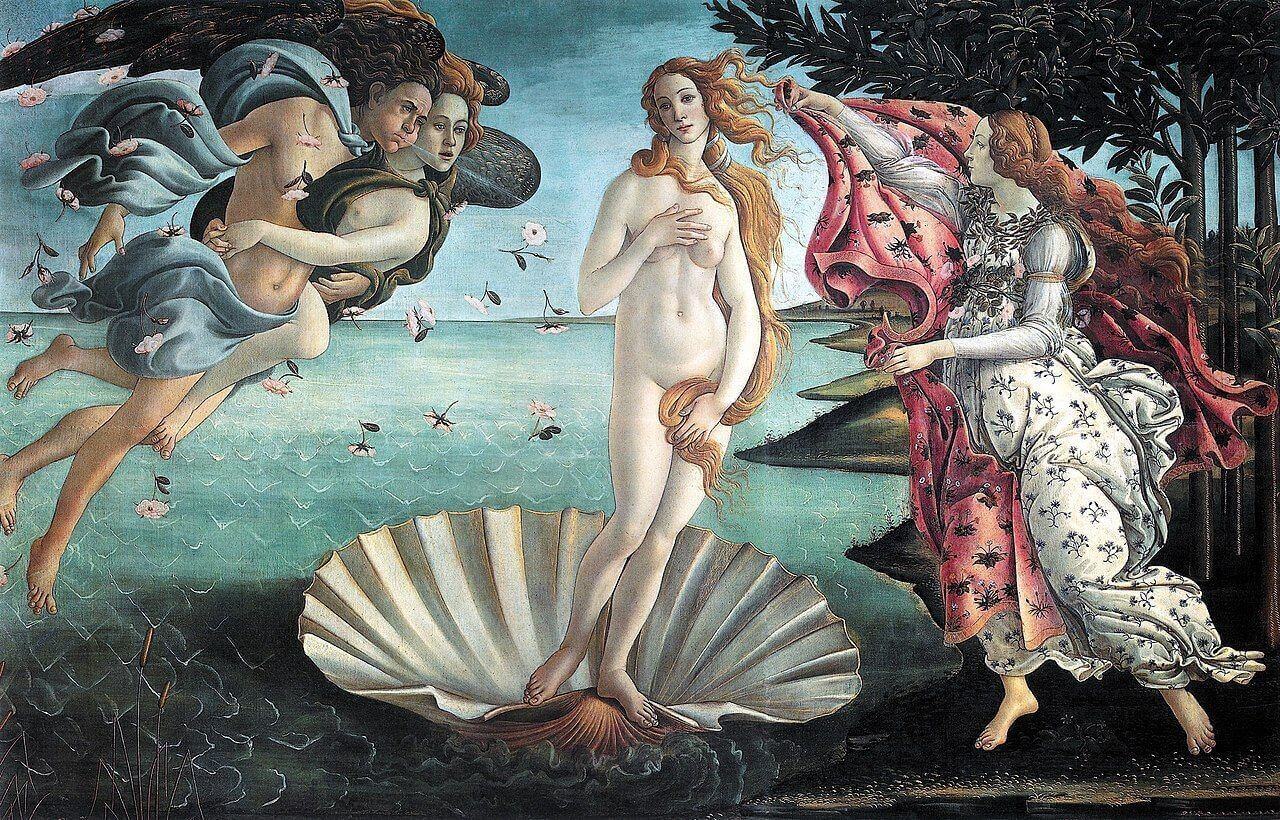

Lucretius’s poem begins with a paean of praise to the goddess Venus, the personification of nature and of creativity, born of the froth and foam of the waves.

Life-stirring Venus, Mother of Aeneas and of Rome, Pleasure of men and gods, you make all things beneath the dome Of sliding constellations teem, you throng the fruited earth And the ship-freighted sea – for every species comes to birth Conceived through you, and rises forth and gazes on the light. The winds flee from you, Goddess, your arrival puts to flight The clouds of heaven. For you, the crafty earth contrives sweet flowers, For you, the oceans laugh, the skies grow peaceful after showers, Awash with light… (1-10)

This lush, rich evocation of the surging abundance of the world soon gives way to a rather more austere picture, deriving ultimately from Democritus, in which the universe is made up of atoms and void. Lucretius images a waterfall of atoms streaming downwards through the void on account of their weight, a constant rain of matter. This makes Lucretius’s universe (unlike that of Aristotle) one in which motion, not rest, is primary. The world, even at the simplest level, is dynamic.

But a universe in which there is nothing besides a dreary rain of atoms, falling in parallel through the void, is not a universe where anything particularly interesting can happen. So Lucretius introduces another element that is both intriguing and also controversial to the point of scandal. What, he says, if you introduce a bit of indeterminacy into the system? What if you allow one of these falling atoms to swerve, ever so little?

Another basic principle you need to have a sound Understanding of: when bodies fall through empty space Straight down, under their own weight, at a random time and place, They swerve a little. Just enough of a swerve for you to call It a change of course. Unless inclined to swerve, all things would fall Right through the deep abyss like drops of rain. There would be no Collisions, and no atom would meet atom with a blow, And Nature thus could not have fashioned anything, full stop. (216-223)

Swerving Suggestion

Throughout history, this idea of a “swerve”, or a clinamen, has been widely derided. As Andrew Pyle puts it, in his book Atomism and its Critics, “The doctrine of the ‘swerve’ was, of course, ridiculed in antiquity as a mere subterfuge, an ad hoc hypothesis invented to save free will.” Pyle’s “of course” suggests that he agrees with this assessment: that the clinamen is an inept attempt to rescue the possibility of genuine choice in a universe that is fully determined.

But if you read Lucretius closely, this doesn’t seem to be what he is up to. When he introduces the idea of the clinamen, Lucretius makes a bigger claim on its behalf. The clinamen is not necessary for there to be free will. Instead, it is necessary for there to be anything at all. Without the swerve, atoms wouldn’t clump and combine, objects wouldn’t interact, there wouldn’t be any beings for whom free will was even an issue, and the universe would be an endless, dreary stream of atoms, going on forever.

In other words, first and foremost, Lucretius’s swerve is about physics, not freedom. Only once those atoms falling through space are capable of a swerve is there the possibility that they may collide, spin off in unpredictable directions, clump together, form themselves into larger and larger bodies… The clinamen is not a way of patching physics to make room for free will. It is an attempt to argue that without a grain of indeterminacy, the world simply wouldn’t exist.

On Free Will and Whimsy

Nevertheless, Lucretius does have something to say about free will. He is the first thinker in the Western tradition to use the term “free will,” and in doing so, he refers directly to the swerve or the clinamen. But his view is much more subtle than the view usually attributed to him. He begins off by linking free will with a kind of internal agency—an inbuilt whimsicality.

Where does that freewill come from that exists in every creature The world over? Where do we get that freewill, wrenched away From the fates, by which we each proceed to follow pleasure’s sway, So that we swerve our motions not at a designated spot And fixed time, but the very place we will it in our thought? Without a doubt these motions have their beginning in the whims Of each, and from that Will these motions trickle into the limbs. [253-259]

Our whims cause us to swerve on our course through the world, to behave in ways that are creative, unpredictable, unforeseeable. Here, Lucretius isn’t claiming that the clinamen is the source of free will. Instead, he seems to be using the idea of a swerve more metaphorically: just as atoms swerve from their fixed courses in unpredictable ways, we too swerve from our seemingly fixed courses, not on account of the atomic swerve, but on account of the “whims of each.” We are unpredictable beings in an unpredictable universe.

However, even though Lucretius doesn’t go so far as to claim that free will is conjured into existence by the atomic swerving of atoms, he does argue that the existence of genuine indeterminacy makes this a universe in which free will is possible—because it means ultimately that the universe is not fully determined. Lucretius says that the fact that,

…the mind Is not bowed by necessity in everything it does And forced to just endure it and to suffer is because Of the slight swerve of the atoms, at a random time and place. [291-294]

Here, Lucretius looks like he is simply being a good Epicurean, and pointing out that in a fully deterministic universe, there is no space for genuine free will. However, in his Letter to Menoeceus, Epicurus takes pains to argue against both necessity and chance as ways of accounting for human agency. A universe governed entirely by necessity would leave no room for genuine choice. But neither would a universe governed entirely by chance. For Epicurus, true agency presents us with a third possibility, which is neither rooted fully in necessity nor in chance. Writing of the prudent person, Epicurus says, “some things happen of necessity, others by chance, and others by our own agency.” For Epicurus, necessity “is not answerable to anyone.” The idea that we are fully determined cannot provide a foundation for any genuine idea of human agency. But neither can chance provide such a foundation because “chance is unstable.”

True agency neither fully belongs to chance nor to necessity. And it is this agency that makes us genuinely autonomous. So for both Epicurus and Lucretius, whatever may be going on at the level of atoms—the cocktail of necessary and chance events—if we want to think properly about human agency, we need to scale things up. Agency happens at the level of human beings, who exist in a universe that is neither fully determined, nor fully ruled by chance. And this agency which makes us genuinely autonomous and morally culpable can ultimately be no more be reduced down to chance than it can to necessity.

Living Between Chance and Necessity

Where does this leave us? It leaves us in a universe that is caught somewhere between chance and necessity, but that is reducible to neither one nor the other. And in this space in between the two, we find a world is a riot of vigorous, proliferating creativity. No wonder Lucretius begins his poem with the image of the goddess Venus: the overseer of fertility, of fruiting and budding, of new life, of the world’s rich abundance. It is a vision of an inherently creative world, throwing up novelty all the time as things grow, develop, bear fruit and pass away, a ferment of creativity in which the “universe’s rich variety” (829) arises out of the simplest of principles.

But if this is the world we live in, what are we to do about it? Like many ancient philosophers, Lucretius was preoccupied not just with saying how the world is or how it seems to be, but with exploring how we might live in the light of this. So this will be the subject of the next piece, when we look at Lucretius’s On the Nature of the Universe as a guide to life.

Notes

All the quotes from Lucretius come from Alicia Stallings’ translation, Lucretius: The Nature of Things (Penguin 2007). I’ve used the EPUB version, so referenced the line numbers in the text.

For quotes from the Letter to Menoeceus, I relied on Brad Inwood and L.P. Gerson’s The Epicurus Reader: Selected Writings and Testimonia (Hackett 1994).

The quote from Andrew Pyle comes from his book Atomism and its Critics (St. Augustine’s Press 1995), p.169.

For another take on Lucretius, read Michel Serres’s fascinating book The Birth of Physics, translated by David Webb and William Ross (Rowman & Littlefield 2018).

Try also Stephen Greenblatt’s excellent The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (W. W. Norton 2011).