Texts and Woven Threads

The tradition of Nyāya philosophy in India goes back to a text called the Nyāya-sūtra. It is one of the most extensive treatments of the art of reasoning to be found in early Indian philosophy.

The Nyāya-sūtra is a fascinating text, one that explores the relationship between knowing, practical action, and doubt. The various strands in the sūtra (the word “sūtra" सूत्र means “thread”) were probably brought together into something resembling the current form around 150 in the Common Era. However, the text almost certainly contains debates, discussions, and ideas that long predate this.

The text as it has come down to us bears the hallmarks of a text that was made to be recited, a part of the oral tradition. It is constructed out of tightly crafted aphorisms that lend it to memorisation and oral transmission.

As for the authorship of the Nyāya-sūtra, it is attributed to a man called Akṣapāda Gautama. If the author existed at all, we don’t know anything about him. Various accounts put his dates around anything from the 6th century BCE to the second century CE when the text reached its current form. The name Akṣapāda means “gazing at the feet.” One colourful suggestion is that this is a reference to how Akṣapāda Gautama spent his days lost in thought, staring at the ground. But there’s no reason to think this is true.

There are many puzzles around the Nyāya-sūtra – how it evolved, when it evolved, who its many authors were, how we can date it. Here, as with so many things, any claims to certain knowledge are unreliable. And it is perhaps appropriate that this is the case. Because these kinds of questions – about what we know, what we think we know, and how reliable our knowledge is – lie at the heart of the Nyāya-sūtra and Nyāya philosophy more broadly_._

Knowing and Acting

The question that the Nyāya-sūtra asks is this: how can we know? The word “nyāya” can be translated as something like “right reasoning.” And the Nyāya-sūtra starts by arguing that the sources of knowledge, or pramāṇas, matter precisely because they are practically useful. __ Here is the gloss provided by the 5th-century commentator, Vātsyāyana.

When an object is comprehended through a knowledge source (pramāṇa), it becomes possible to engage in successful goal-directed activity. Thus, a knowledge source is useful (arthavat). Without a knowledge source, there would be no effective cognition of an object. Without such cognition, there would be no successful action. [1]

This concern with knowledge is no idle philosophical speculation. Instead, knowledge matters because if we start from the point of view of knowledge that is unsecured, or just plain wrong, we will end up setting our sights on the wrong kind of goals, or failing to reach the goals we aspire to. Knowledge underpins action. And so if our approach to knowledge is messed up, then our actions will fail to be effective.

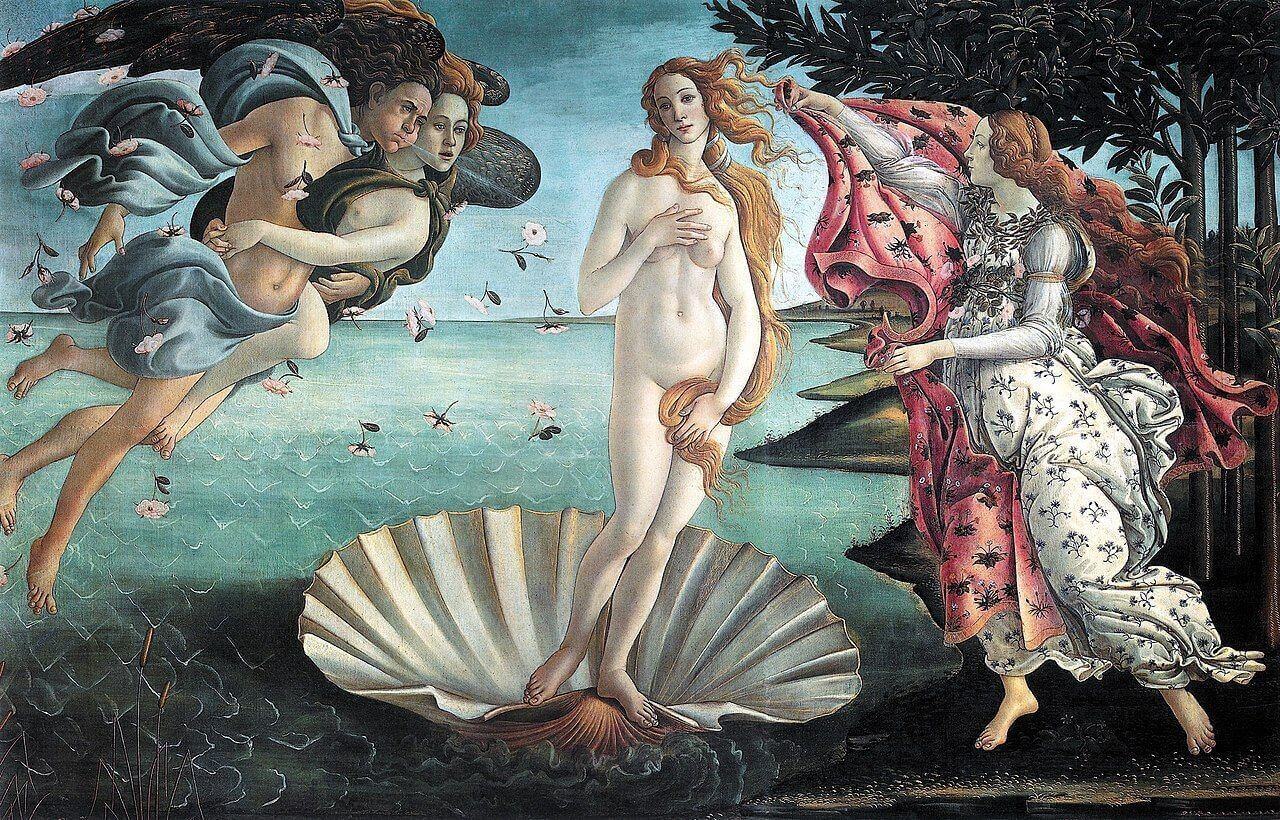

For the Nyāya philosophers, knowledge is a process. In the Nyāya system, knowledge isn’t a store of information on which we can draw. We don’t possess knowledge the way a squirrel might possess a hoard of nuts. Instead, knowledge involves repeatedly coming-to-know. It is a dynamic process, one that allows us to attain our goals, whether these are worldly (accumulating wealth and power, for example), or more ambitious (liberation from rebirth).

Squirrel. Late 1800s. Boston Public Library, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Squirrel. Late 1800s. Boston Public Library, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Reliable Knowing

This being the case, the Nyāya philosophers are preoccupied with the question of the reliability of this process of coming-to-know. In this sense, knowledge is like a vehicle: it gets us places. And a vehicle that is broken, or that is unreliable, or that works badly is going to get us precisely nowhere.

In its exploration of what it means to know reliably, the Nyāya-sūtra proposes four sources of knowledge (pramāṇas). These are perception (pratyakṣa), inference (anumāna), analogy (upamāna) and testimony (śabda). We come to know things, in other words, by perceiving them, by drawing inferences from other things, by making analogies, and by relying on the testimonies of others.

Perception is the basis of the whole system. For the Nyāya philosophers, perception is the meeting of a sense faculty (for example, the sense faculty of seeing) and an object (for example, a squirrel). Inference depends upon perception: if we are to draw inferences, first we have to perceive things. We perceive swollen clouds, and we infer that it will rain (this is inference “from something prior” because the swollen clouds precede the rain). We perceive a swollen river and infer that it has been raining upstream (this is inference “from something later”). Analogy is about shared properties (“a buffalo is like a cow” is the example given in the text). It is a way of knowing through similarity with something familiar (and so is also anchored in perception). And finally, testimony is the word or instruction of a trustworthy authority for whom knowledge, presumably, also begins in perception.

Of course, not all perceptions, inferences, analogies, and testimonies are reliable sources of knowledge. But having divided up potentially reliable sources of knowledge into these four categories, the Nyāya philosophers can then explore in more detail questions about how these four processes work – or how they break down.

Sunstroke and Philosophy

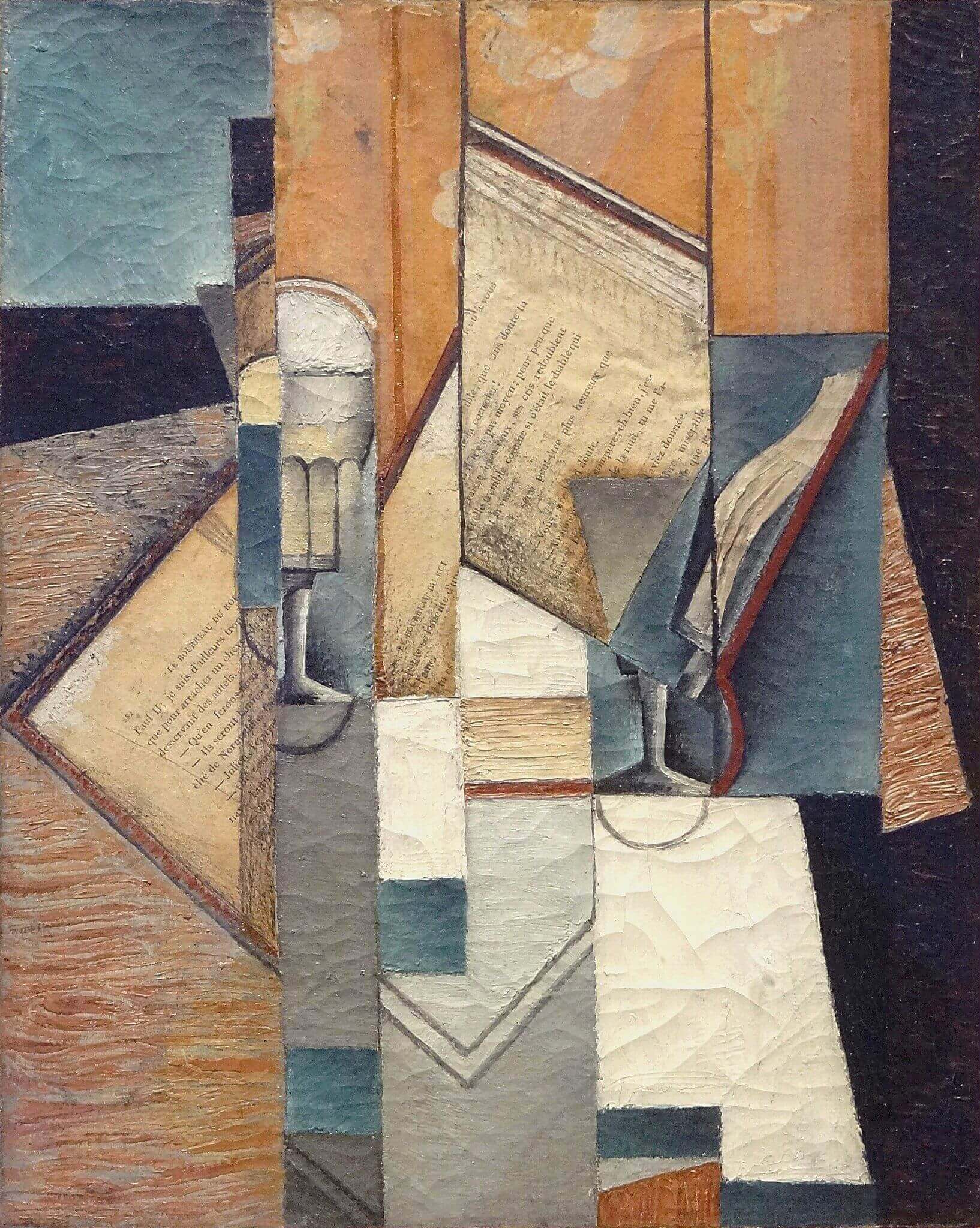

Here’s an example of one such breakdown in ways of knowing. A couple of years ago, while on the Bulgarian coast, I had heatstroke. I was walking back to my hotel with friends, and suddenly my everyday experience of the world started to glitch. It was really weird. When I turned my head, the world fragmented. My vision was all over the place. Everything was like a Cubist painting.

Le Livre by Juan Gris (1911). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Le Livre by Juan Gris (1911). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

On that day in Bulgaria, I went back to my hotel room, lay down, cooled off, and drank water. In about an hour or so, I had recovered. But the sheer weirdness of this breakdown in perception stayed with me.

It was pretty dramatic, but we all have less dramatic experiences than this every day. For example, one day you are in the park, and you see a squirrel scampering around under the tree. You think you are seeing everything about it: its fur, its plump body, its little beady eye, its tail. But when you get a couple of steps closer, you realise it isn’t a squirrel at all: it is a tin can.

So perception is not reliable. Or not always. Nor are inferences. We can draw successful and unsuccessful inferences. As for analogies, sometimes analogies help us, but every so often (more often than we might like) they lead us astray. And we all know that testimony can be flawed and that this too can fail us.

When to Doubt, and When Not To

This raises the question of when we should doubt these processes of coming-to-know, and when we should just go along with things. Going around the whole time doubting our perceptions, our inferences, our tendencies to draw analogies, and the testimony of others is both exhausting and counter-productive. It takes time and effort. And it gets in the way of getting anything useful done. If you didn’t rely on testimony, you’d never step on a plane. If you didn’t rely on your perceptions, you would be able to move around the world. If you couldn’t draw inferences, you couldn’t think very much at all. And human thinking is irredeemably analogical and metaphorical, so we can’t do without analogy either.

So when should you doubt these sources of knowing, and when should you just go along with things? The Nyāya answer is refreshingly straightforward: you should doubt when you have a legitimate reason to do so. When the world glitches due to heatstroke, for example. You should doubt when you stumble across something that gives you pause, and makes you question the sources of your knowing.

We simply can’t go round making sure we’re absolutely certain about everything all the time. If there is good reason to trust the processes of coming-to-know, there’s no point in doubting. But when there is a glitch, a gap, a tension, a contradiction, a puzzle, this is when doubt comes into play. It is the point at which you say, “Hold on. This doesn’t look right…” Then you go seeking more details about what exactly isn’t right, or what exactly isn’t clear. Doubt comes in at the point at which something prompts further investigation. Doubt, the Nyāya-sūtra says, is “deliberative awareness in need of details about something particular.” [2]

Getting Things Done With Nyāya Philosophy

Like many early Indian traditions, the ultimate goal of Nyāya philosophy is liberation. But even if we have our sights set on less lofty goals, the Nyāya approach to knowing is a useful one. When things don’t look quite right, when you feel some sense of legitimate doubt creeping in, when the world begins to glitch and you suspect sunstroke, these are useful questions to ask:

- What are my perceptions, and how reliable are they?

- What inferences am I drawing, and how reliable are they?

- What analogies am I making, and are they helpful?

- To what extent am I relying on the testimony of others, and how reliable is this testimony?

Even if your ultimate goal is not liberation from the endless rounds of rebirth (which was the goal of the Nyāya philosophers), these questions can help us navigate through the world. Because if we care about the practical ends of human life, we can’t avoid asking about the reliability of perception, inference, analogy, and testimony.

Notes

[1] Nyāya-sūtra: Selections with early commentaries, translated by Matthew Dasti and Stephen Phillips (Hackett 2017), p. 14

[2] ibid. p. 41

Further Reading

Books and articles

Matthew Dasti and Stephen Phillips’ translation published by Hackett (2017) is excellent and clear.

For an accessible (but much more in-depth) exploration of Nyāya philosophy, try Peter Adamson and Jonardon Ganeri’s Classical Indian Philosophy (Oxford University Press 2020).