It’s a curious image. The philosopher Plato, dressed in a turban and a sash, sits before a pipe organ and plays sweet tunes. Meanwhile, around him lies a catatonic tribe of lions, tigers, antelopes, leopards, deer, rhinos, cranes, phoenixes and other beasts. What’s going on here? Are these animals sleeping? Are they dead? What is Plato up to?

It’s a strange and fascinating scene, so yesterday — not having much else to do under lockdown — I set about finding out more.

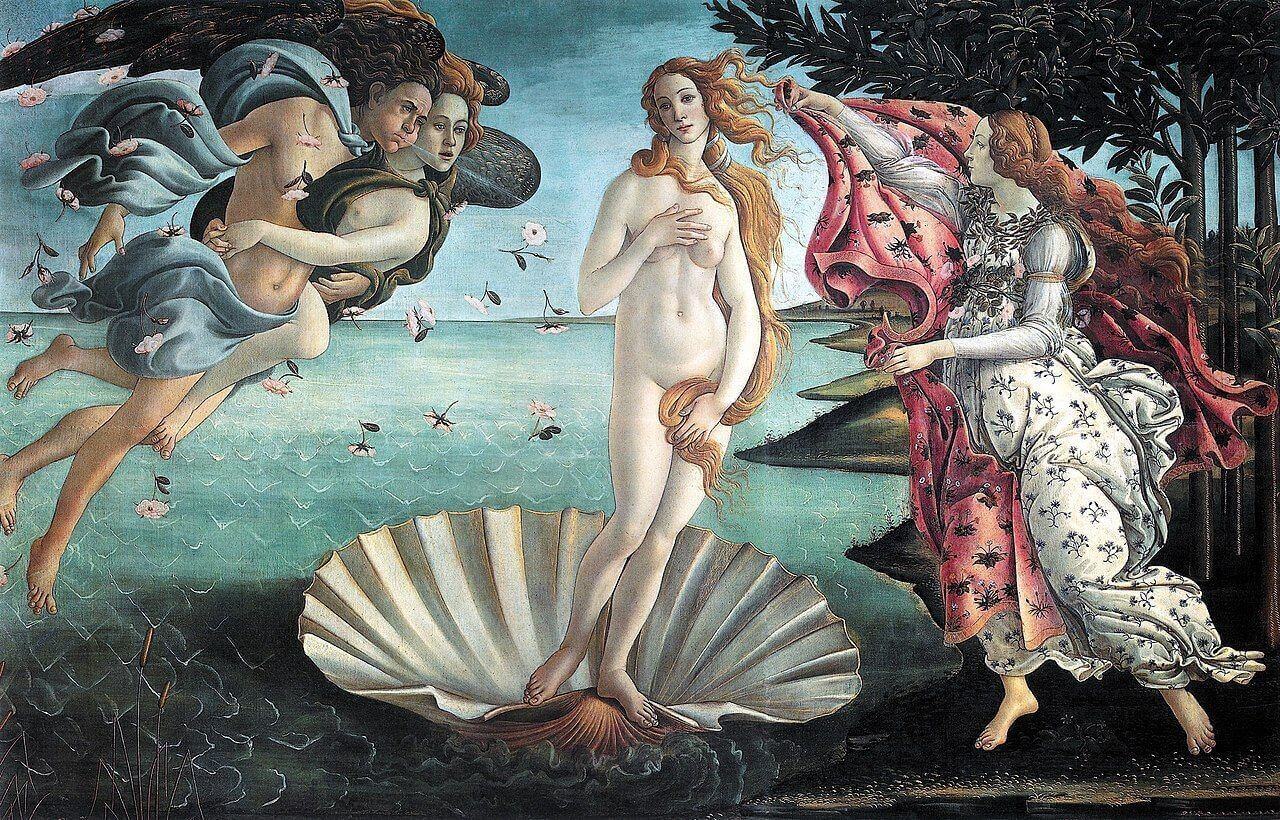

It is not a scene you will find in any of the Greek texts. The image, now in the British Museum, is attributed to the Mughal painter Madhu Khanazad at the end of the sixteenth century. It is an illustration of a part of the Persian book of Sufi poetry, the Khamsa of Nizami, which in turn dates to around 1200. Here’s the full picture.

Nizami’s Khamsa is particularly famous for the love story of Layla and Majnun. This scene of Platonic music-making occurs later on in the book, in the section dedicated to the exploits of Alexander the Great. In Nizami’s story, Alexander calls together a bunch of philosophers. Then he challenges them to a contest to prove who is the wisest. At first, it looks as if Aristotle is going to win, but then Plato gives a strange musical demonstration, and he eventually takes the prize.

The story is a fascinating one because of the picture it paints of medieval Islamic views of Plato and Aristotle. Plato is reinvented as a mystic, by way of Neoplatonism and Sufi illuminationism or hikmat-i ishrāq, which was in the ascendant in Persia at the time the book was written.

I couldn’t track down an English version of the story, but I did find a version in German by J.C. Bürgel. So my English retelling is based on Bürgel’s (see the references at the end). It sticks pretty close to the original text.

Plato Makes Music to Shame Aristotle

Adapted from the Khamsa of Nizami

The ruler Alexander, whose tongue and mind were like flame and candle-wax, summoned the philosophers of his empire to a debate, to see who was the greatest. In the palace, the philosophers sat at the foot of Alexander’s throne in a line. And there they talked about logic and magic, mathematics and art, theology and science. But after every philosopher spoke, the great Aristotle always found something else to add: some extra subtlety, some further thought

The philosophers were awed by Aristotle’s wisdom and insight. “I am the leader of all in matters of wisdom,” Aristotle bragged. “This judgement is not a lie. It is not arrogance. It is simply how things are.” And Alexander was inclined to agree.

But Plato, who had not yet spoken, was indignant. He made himself scarce and fled the palace, the way a phoenix can suddenly disappear. He took himself to a solitary place and hid himself away in a barrel. There in his lonely retreat, Plato followed the traces of the spheres and tracks of the stars. He listened for their harmonies, traced their pattern.

When he had complete knowledge of the sounds, Plato made a musical instrument, fashioning wood, making strings, stretching gazelle-leather over a gourd, and rubbing the skin with musk so the sounds were sweet. When he was done, he had made a contraption that could sing out high and low, in loud and soft tones. His instrument could emulate the sounds of all living beings — even the lion and the ox — a music that could speak to the individual nature of every living thing, could testify to their suffering and joys.

Plato went out into the desert, taking his strange contraption with him. He drew a circle around himself and sat down. Then he began to play. The moment he did so, the wild animals from the mountains and the plains all came running. They put their heads down on the line that Plato had drawn, lost their senses, and collapsed to the ground as if dead. Wolves and lambs, lions and wild asses: they all snoozed peaceably next to each other.

Plato’s music of the spheres could do this: whether you were an ass or a lion or a human being, it could bring you to a sleep so deep it was almost like death, and then it could revive you and you could go on your way refreshed.

The news of this wonderful music spread quickly, as far as Alexander’s palace. When Aristotle heard about Plato’s skill, he was plunged into depression. How could he be so outdone by his predecessor? So he brooded in the dark of Alexander’s castle, and after long reflection, his keen mind penetrated all the way to the bottom of Plato’s sublime art. He made a musical instrument of his own, and he hurried out to the desert to give it a try.

Aristotle’s instrument more or less worked. He could lull anybody to sleep, just as Plato could. But stirring them back to life turned out to be a bigger problem, and no matter how much Aristotle struggled to find the right mode or harmony, he failed.

So in the end, Aristotle swallowed his pride and went to see his teacher Plato: “I know the mode that lulls people into unconsciousness,” he said, “but I do not know the one that brings the spirit back from its sleeping.”

Plato offered to teach Aristotle his art. Again Plato drew a circle about them both, and he started to play. Again the animals came running, put their heads on the line, and fell asleep. Aristotle more or less knew how to do as much, and was not greatly impressed. But then Plato modulated into a new key. The music was sweet as nectar, and Aristotle immediately lost consciousness. Whilst Aristotle was passed out, Plato changed key again, and he woke up the animals. Once the animals were restored to consciousness, Plato woke Aristotle.

Aristotle got to his feet like a ray of fire, confused by what had happened, annoyed he had missed Plato’s profound teaching. But then seeing he was outwitted, he apologised for his arrogance, and praised Plato for his greater powers.

Only then did Plato teach the much chastened Aristotle what it meant to play the modes that reflected the harmonies of the heavenly spheres. And from then onwards, Aristotle never ceased praising Plato for his greater wisdom. As for Alexander, when news of Plato’s demonstration reached him, he showered honours upon the older philosopher, acknowledging him as the wisest man in all Greece.

References:

My retelling is taken from the German translation in “Der Wettstreit zwischen Plato und Aristoteles im Alexander-Epos des persischen Dichters Nizami” by J.C. Bürgel, Die Welt des Orients, Bd. 17 (1986), pp. 95-109.

There’s also an essay by Bürgel in The Poetry of Nizami Ganjavi: Knowledge, Love, and Rhetoric, edited by Kamran Talattof and Jerome W. Clinton (Palgrave 2000).