Plato’s so-called ’theory of forms’ is one of the most enduringly strange parts of his philosophy. It is also one of the main centres of gravity around which Plato’s work turns. So in the second part of our two-part philosopher file on Plato, we’re going to look at this theory in more depth.

If you want more background information on Plato, you can go to part one and read the piece there. But for now, we’re going to plunge right in, and we’re going to try to figure out what Plato’s theory of forms is all about.

More or Less Ideal Cats

One reason that Plato’s theory of forms can be hard to get hold of is that Plato never sits down and says, ‘Okay, I’m now going to tell you my theory of forms.’ Instead, while he refers to these mysterious forms repeatedly, sometimes even discussing them at length, he never tells us exactly what he means.

As a result, in the centuries since Plato, philosophers have disagreed about the nuances of Plato’s theory. But most of them have agreed that his theory of forms is a way of thinking about the relationship between two things. On the one hand, there is the messy, untidy world that we access through our sense experience. And on the other hand, there is the world of ideals that we access through the intellect.

But to help us get to grips with this, let me start with a story. Here in Sofia, where I’m currently living, we recently fostered a cat. He was a handsome fellow, with long ginger hair and golden eyes. The rescue people called him Aslan, and as we were only short-term carers, we kept the name.

Before Alsan arrived, the rescue organisation told us he was the ideal cat—as close as a cat can be to being a paragon of perfection. He was friendly, he was well-behaved, and he was strikingly good-looking. And all this turned out to be true: once Alsan moved in, we were immediately smitten. Here he is, just for the record.

Soon after Aslan settled in, the cat rescue people got in touch again. They were looking to rehome another cat. And they told us they had a plan. As Aslan was a particularly fine specimen, an almost-perfect cat, they said they would see if they could find an ugly companion cat to bond him with. Then they could rehome the two cats together. Ugly cats, they said, are harder to home; but if they come with beautiful companions, people are willing to take them in.

This seemed problematic in all kinds of ways. But we liked the idea of having an ugly cat in the household, so we agreed. When it came down to it, there were no ugly cats available. So, when cat number two turned up (he had been rescued from an aspen tree, and so was called Aspen), he was hardly a bad-looking character. He was sweet and not unattractive, and very friendly. But although we loved him and Aslan equally, it was also clear to us that Aslan was the more perfect of the two beasts—the closer to the ideal cat (if such a thing can be said to exist).

The two boys got on very well, and after a few more weeks living with us, they were transported to their new long-term home in Germany. And after they had gone, I was left with a philosophical question: what makes a cat more or less ideal, or more or less perfect? What do we even mean when we say this?

Feline Forms

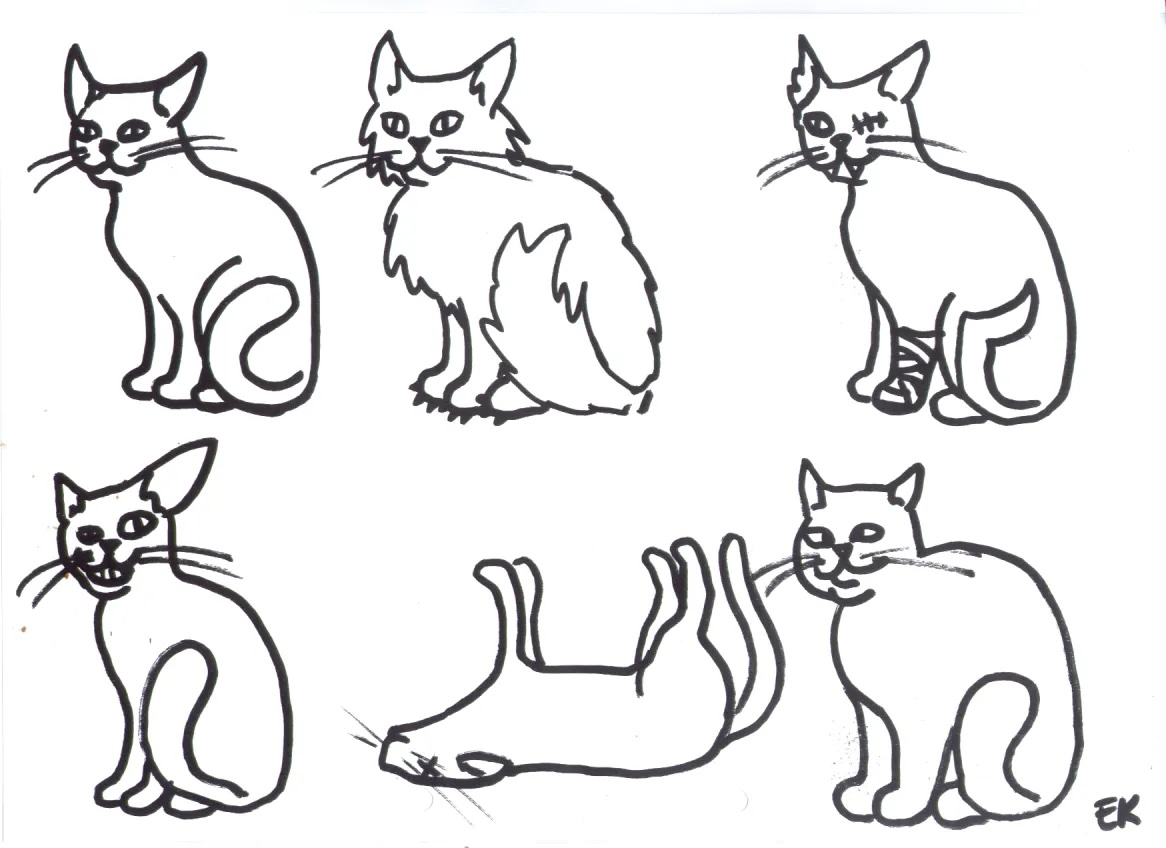

The answers to these questions will lead us straight to Plato’s theory of forms. So let’s have a look at this little diagram depicting six cats (drawn by the late, great Elee Kirk). Imagine them numbered one to six, starting at the top left and ending at the bottom right.

Before we start discussing these cats in detail, it’s worth pausing to ask how we know that this is a picture of cats, and not of dogs or of lemurs or of members of parliament. One answer to this is that we know because these drawings correspond, to a greater or lesser degree, to the mental image we have of what a cat is.

But also, in looking at these cats, you may also have already decided that they are not all equal in their perfection. In fact, some are decidedly more perfect than others.

I’ve used this picture when teaching a lot in the past, and I often ask my students to tell me which is the most perfect or most ideal cat. At this point, some people say, ‘I like no. 3’ (the piratical cat with a missing eye). Or they say, ‘cat no. 4 is cute’ (the lopsided one). And that’s fine. We might prefer these cats. But in saying that no. 4 is lopsided, or no. 3 is missing an eye, we’re also committing ourselves to the idea that the ideal cat is symmetrical, or has two eyes. Cat no. 3 and cat no. 4 may be cuter, but they are less perfect because they depart from the ideal.

So which is the most perfect cat? Here, most people equivocate between no. 1 and no. 2. After all, no. 5 is dead, which is something of an imperfection. And no. 6 is a bit cross-eyed, so also diverges from the idea we have in our minds of what it is to be a perfect cat.

In other words, when we come across cats in the world (or drawings of cats), we evaluate how ideal or perfect they are by comparing them with the idea (or, as Plato sometimes puts it, with the form) of what a perfect cat is. And this idea or form of a cat is not something we access with the senses. It is something we access with the mind.

Perfect Forms and Imperfect Sandwiches

In this way, Plato divides the world into more or less imperfect things that we apprehend through the senses, and perfect things (forms or ideas) that we apprehend through the intellect. It is a move that comes from his interest in mathematics. So let’s move from talking about cats to talking about triangles.

A triangle, you will remember from school, is a mathematical object with three straight sides, the angles of which (assuming that it is on a plane) add up to 180 degrees. There are a few things to notice here.

First, this is true by definition, which means it is also timelessly true. It is true independent of any actual triangles in the world. If the universe was reduced to a shapeless rubble—a fine dust without anything being obviously any shape at all—the truth of the definition of a triangle would still hold.

Second, the idea (or the form) of the triangle is not something we apprehend by seeing, but instead something we grasp by the power of the intellect. When we understand that a triangle is a three-sided polygon, we have grasped the essence of what a triangle is—not with our senses, but instead with our minds.

And third, the various triangular things in the world we come across only at best approximate to this ideal definition of a triangle. These tasty-looking sandwiches, for example, are only approximately triangles.

The most real, most substantial triangle is not the sandwich in front of us. Instead, it is the triangle we can grasp with the mind. This is the eternal form (or idea) of the triangle, of which sandwiches, pyramids and other imperfect worldly things are only dim reflections.

The Form of the Good

While Plato’s arguments from mathematics may seem pretty convincing, when it comes to particular things in the world like cats, the theory of forms becomes a bit harder to make sense of. Is there one form for black cats and another for ginger cats, or is there only one form for cats in general? Does Aslan (handsome fellow that he is) participate in the form for ‘cats’, or for ‘domestic cats’ or for ‘mammals’ or for ‘quadrupeds’, or for all of these? This was a question that Plato’s student Aristotle raised in his Metaphysics. Aristotle realised that when you start to pick away at the question of how many forms are there for any one thing, things rapidly become complicated.

But Plato was never really very interested in things like cats and dogs. He was much more interested in taking his insights from mathematics to tackle bigger, more pressing questions—like questions of ethics. And the thing he cared about above all else was what he called the form of the good (or, in Greek, ἡ τοῦ ἀγαθοῦ ἰδέα).

What is this mysterious ‘form of the good’? If we go back to Plato’s early dialogue, the Euthyphro, we find Socrates worrying about the subjects over which we human beings fall into dispute. If we fall out with each other, it is not because we disagree over things we can resolve by measurement, or through the evidence of the senses. If you say there are ten sandwiches on the plate, and I say there are eleven, then we can resolve our dispute amicably by counting the sandwiches.

So, what things do we fall out over? They are usually questions like these: What makes a good sandwich? Should tuna ever be allowed in a sandwich? Whom do these sandwiches belong to? By what right did you eat the sandwich I had put aside for my lunch? And so on. The questions we fall out over are questions about good and bad, justice and injustice.

From the very early Platonic dialogues, Socrates roams around in a ceaseless quest to get to the heart of these kinds of questions. He asks what is justice?, or what is goodness? And in asking these kinds of questions, he doesn’t want just an example of just behaviour or of a good action. He wants to know the essence of justice. He wants to know the unchanging, eternal form of justice.

Plato’s gamble is this: what, he wonders, there is such a thing as an ideal form of the good, one that we can access by means of the intellect—just as we can access the ideal form of a triangle by means of the intellect? If we could only get hold of that, then we could resolve our disputes with ease. And we could organise ourselves in perfect harmony. Goodness and justice would prevail. And many of our deepest human problems would be solved. Or at the very least, we would all behave a lot more sensibly.

‘This is how I see it,’ Socrates says in the Republic (VII 517 b-c):

In the knowable realm, the form of the good is the last thing to be seen, and it is reached only with difficulty. Once one has seen it, however, one must conclude that it is the cause of all that is correct and beautiful in anything, that it produces both light and its source in the visible realm, and that in the intelligible realm it controls and provides truth and understanding, so that anyone who is to act sensibly in private or public must see it.

Further Reading

There’s so much more that could be said about Plato’s forms. This is a tricky area of Plato’s philosophy (what area of philosophy isn’t tricky?), and there’s a risk that everything you say about it going to be either wrong, or only partially true, or at least contentious. But the following books and links will give you a way into some of the debates.

Books and articles

Julia Annas’s Plato, A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press 2003) is a nice introduction.

Quite a few academic publishers have handy ‘companion to Plato’ volumes. The Continuum Companion to Plato edited by Gerald A. Press (Continuum 2012) has a nice, easy introduction to Plato’s theory of forms.

There are lots of translations of Plato available. He’s a surprisingly readable writer (even if the twists and turns of argument can be sometimes hard to follow). I usually use Plato: Complete Works edited by D. H. Hutchinson (Hackett 1997)

Online Resources

Have a read of this piece about the form of the good on 1000 word philosophy.