Cultural connections

The philosopher Pyrrho (c. 360 — c. 270 BCE) was born in Elis in Western Greece. Much of what we know about him is hearsay, deriving from the somewhat breathless accounts of his student and all-round biggest philosophical fan, Timon of Phlius. Timon’s stories, whether true or not, were later taken up by the biographer Diogenes Laërtius. Diogenes supplemented Timon’s admiring accounts with some intriguing tales about Pyrrho’s eccentricities taken from the writer Antigonus of Carystus.

According to these unreliable accounts, Pyrrho’s family trade was the art of divination; but Pyrrho himself started life as a painter, not entirely successfully. He took to philosophy after coming across the atomist ideas of Democritus. The person responsible for this was probably Anaxarchus, a some-time student of Democritus’ with whom Pyrrho travelled to India. Between 327 and 325 BCE, the two of them set off on a road-trip with Alexander the Great’s army as far as Northwest India, or modern-day Pakistan.

With the naked philosophers

The accounts suggest that Pyrrho’s road-trip was both personally and philosophically transformative. In Northwest India, Pyrrho met with some philosophers whom the Greeks called gymnosophists — literally “naked wise men.” And Pyrrho was impressed by their austere, philosophical mode of living.

The gymnosophists were less impressed, however. One account suggests that they told Anaxarchus and Pyrrho they would never attain to wisdom if they fawned before kings such as Alexander. Pyrrho took this to heart, and decided to change his life.

Pyrrho returned home to Elis, where he took up a life of poverty and simplicity. He cultivated an indifference to worldly things. Diogenes Laërtius tells us how Pyrrho happily participated in housework, something unthinkable for a man of his station and class.

This apparent indifference to status was paradoxically fruitful. The traveller Pausanias says that the people of Elis erected a statue in Pyrrho’s honour. Other accounts say that he was made a high priest, in recognition of his piety.

Philosophy

The problem with ethics

One of the best sources on early Pyrrhonism is an account written several hundred years after Pyrrho’s death, in the 1st century BCE, by the philosopher Aristocles. According to Aristocles, Timon (and thus Pyrrho) said that happiness rests upon the answers we give to three different questions:

whoever wants to be happy should consider these three questions. First, how things [pragmata, or “ethical questions”] are by their nature; second, in what way we should be disposed towards these things, and lastly, what will happen to those so disposed. [1]

The question here is one of how we should dispose ourselves towards ethical questions. How should we think about ethics? How should we proceed when facing these questions?

Pyrrho says these kinds of ethical questions (questions like, “Is it right to eat meat?”, “Should philosophers be naked at all times?”, “What is goodness?” and so on), are characterised by three things. They are indifferentiable. They are unmeasurable. And they are undecidable.

[Pyrrho] declared that things are equally indifferentiable and unmeasurable and undecidable (adiaphora kai astathmêta kai anepikrita); because of this neither our perceptions nor opinions tell the truth or lie. [2]

And this is a problem. Because when we make ethical claims, we are doing so on the assumption that precisely the opposite is true. We assume we know what we are talking about, or that we can ultimately establish the truth of what we are claiming. But we don’t and we can’t.

The undecidability of ethical questions goes back to Socrates and his dissatisfaction with the ethical hunches of his contemporaries. But Socrates always told his fellow philosophers to keep on looking for agreement.

Pyrrho took another angle. Ethical questions for Pyrrho are in principle impossible to differentiate (adiaphora). They are in principle not questions about anything measurable (astathmēta). And they are in principle things that cannot be decided upon (adiaphora).

Disentangling ourselves from ethics

Notice all those negations! Pyrrho is far more interested in telling us what cannot be done than he is in telling us what can be done.

But Pyrrho is also raising an important issue. Think of the heat and fury that is generated by discussions about ethics. It is hard to think of anything besides ethics — questions of right and wrong, justice and injustice — that generates such heat and fury. And if these things are so hard to decide upon, this puts us in a perilous position (something Socrates also knew). We can’t decide on these questions; but these are the very questions where our inability to decide leads to difficulty and conflict. So how should we dispose ourselves towards these pragmata? What attitude should we adopt when faced by this undecidability?

There are two possible responses to this. One is, like Socrates, to continue looking for an answer to these questions, to try to disentangle them. The other is to give up on seeking out answers altogether. If ethical questions are a tangle, then it may be that we can’t disentangle them or sort them out. But at least we can disentangle ourselves from these questions. This means that for Pyrrho, instead of trying harder to get to the bottom of things (as Socrates advised), the best solution is to simply step away.

we must be without opinions, and lean to neither side, and remain unwavering (adoxastous kai aklineis kai akradantous) [3]

Again, Pyrrho bombards us with negations. We must be without opinions. We must be without inclinations. And we must be without any kind of wavering. If this is a kind of ethics, it is a kind of ethics expressed entirely in the negative.

A strange freedom

As for where this all gets us, once again, Pyrrho talks in negatives. “What remains for those who have this attitude,” he says, “is first unspeakingness (aphasia), and then undisturbedness (ataraxia).”

The first of these, aphasia, is a little obscure. What is unspeakingness? Some scholars claim it is the unwillingness to commit oneself verbally to any specific position. But others claim that for Pyrrho, it means literally silence. Why silence? Perhaps because once you have done away with all of this ethical chatter, there is really nothing much to say.

The other idea of ataraxia — undisturbedness, or freedom from disturbance — is one that become important to later Greek philosophy as a goal for life, in particular in the work of the Epicurean philosophers. Because once you step outside of debates around what is good and what is not, you are left with a profound tranquillity: something that early account of Pyrrho’s own character attest to.

Was Pyrrho a sceptic?

For some, Pyrrho stands at the origins of the Greek and Roman philosophical school of scepticism. But although the later sceptics traced their roots back to his thinking, Pyrrho himself seems less concerned with knowledge-claims than later sceptics. Instead, he seems more concerned with pursuing a mode of existence in which he cultivated a form of disengagement and disentanglement. It’s only with later writers such as Sextus Empiricus (who flourished around 200 CE, half a millennium after Pyrrho) that scepticism as we know it takes on its full form. But we’ll get to the later sceptics in a later Philosopher File. So stay tuned!

Notes:

[1] Quoted in Svavar Hrafn Svavarsson, “Pyrrho and early Pyrrhonism”, The Cambridge Companion to Scepticism (Cambridge University Press), p. 41

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

Further Reading

Books

Christopher Beckwith’s Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia makes strong claims about the influence of Buddhism on Pyrrho’s thinking. The book has been controversial; but even if you are a sceptic when it comes to Pyrrho as the Greek Buddha, Beckwith gives a very clear account of Pyrrho’s thinking.

The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Scepticism edited by Richard Bett (Cambridge University Press 2010), is a good starting point.

The other good introduction is Ancient Scepticism by Harald Thorsrud (Acumen 2009).

If you want an entertaining — and unreliable — account of Pyrrho’s life, try Diogenes Laërtius: Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, translated by Pamela Mensch (Oxford University Press 2018).

Online Resources

For a good discussion of Pyrrho and his sceptic successors, try this episode of the BBC show In Our Time.

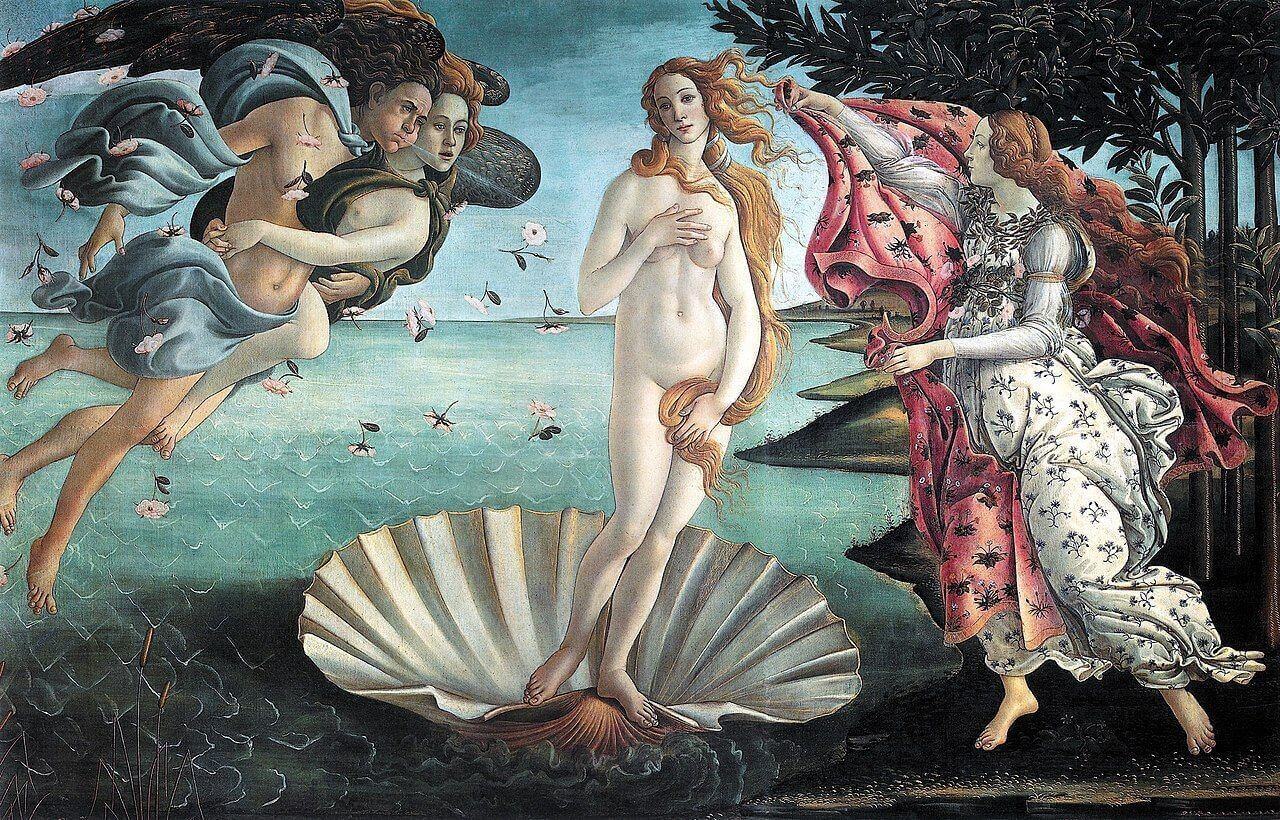

Image: Pyrrho on a sea voyage, remaining calm even in the midst of a storm. Image early 16th century. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.